You receive a gift from your scientific hero Charles Darwin. It is a book that contains sections on your favourite topic-ants. If only you had paid attention when your mother tried to teach you English you might be able to read it. But you didn't, and you can't.

This was Auguste Forel's dilemma when Darwin sent him a copy of Thomas Belt's The Naturalist in Nicaragua (1873). Darwin clearly assumed that Forel, a young Swiss physician working in an asylum in Bavaria, would be able to read the book, even though Forel corresponded with him in French and had used that language to write a book on Swiss ants. He had also admitted that he had to get Darwin's letters translated. It was not a lack of linguistic proficiency that held Forel back. He was a German speaker but preferred French. In fact, he liked French so much that he wrote numerous love letters in that language to his fiancée before realising that she could barely understand a word.

Writing in French on 12 November 1874 to thank Darwin for the book, Forel admitted that he had managed to get the gist of Belt's observations on ants only with the help of an English speaker. This relatively nondescript letter is a favourite of mine because it is a perfect example of how much can lie beneath the surface of a letter.

The English speaker was Emma To de Horst, the head nurse of the Oberbayerischern Kreisirrenanstalt München (Upper Bavarian District Mental Asylum Munich), where Forel worked as an assistant physician. She agreed to teach Forel English over a cup of tea in the ward every morning from eight to nine, using Belt's book as the basis for the lessons. 'By the time we finished it', Forel recalled in his memoirs published sixty-three years later, 'I could read English pretty fluently, and in time I even learned to speak it after a fashion. For this Darwin was responsible, and I have been grateful to him all my life.'

Women like Emma To de Horst (credited by Forel in his letter and named in his memoirs) are not always lost in translation, although they are not always noticed. Victorian men often regarded wives and daughters as helpmeets, but only occasionally acknowledged their assistance. It is mainly private letters that allow us to re-evaluate the skills women brought to the scientific enterprise, not least as translators. The Darwin correspondence reveals that many men of science (including Darwin) depended on the linguistic skills of women.

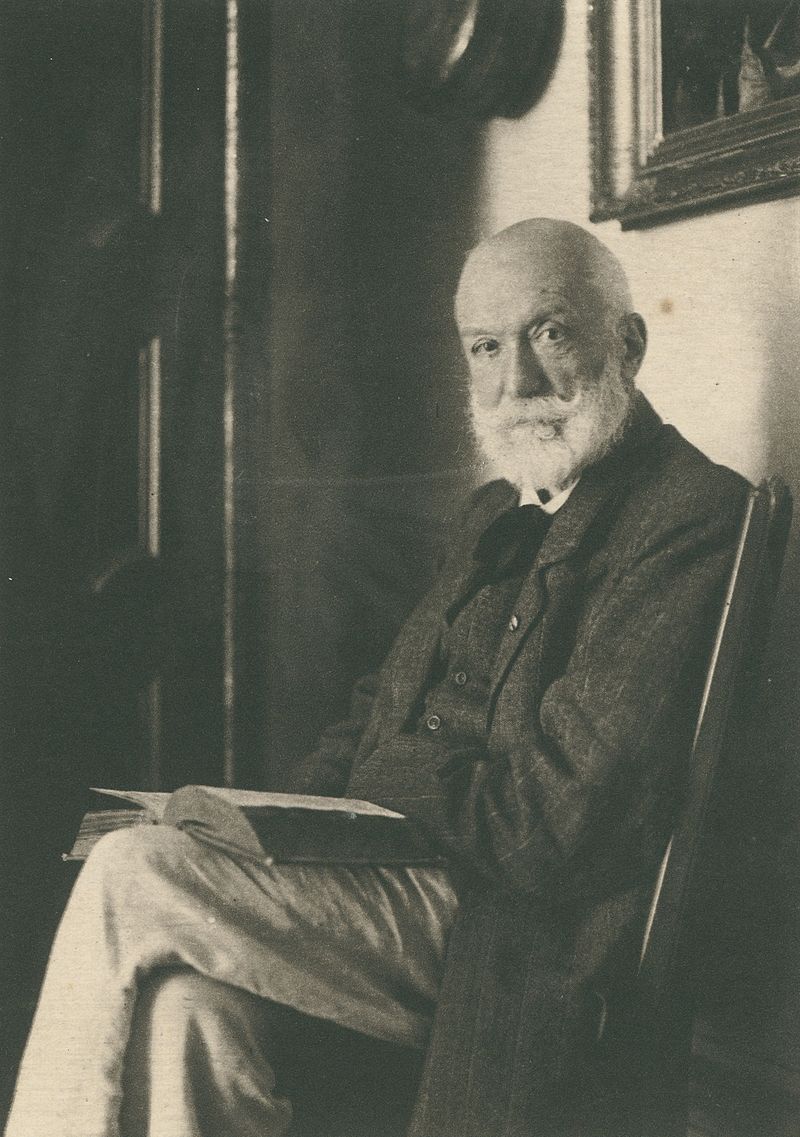

Anne Secord