9 July - 3 December 2022

Milstein Exhibition Centre, Cambridge University Library

09.00-18.30 Monday-Friday

09.00-16.30 Saturdays (closed Sundays)

Free and open to all - Book your tickets here

Groups are welcome - please email events@lib.cam.ac.uk to discuss your visit

Meet Charles Darwin as you have never met him before.

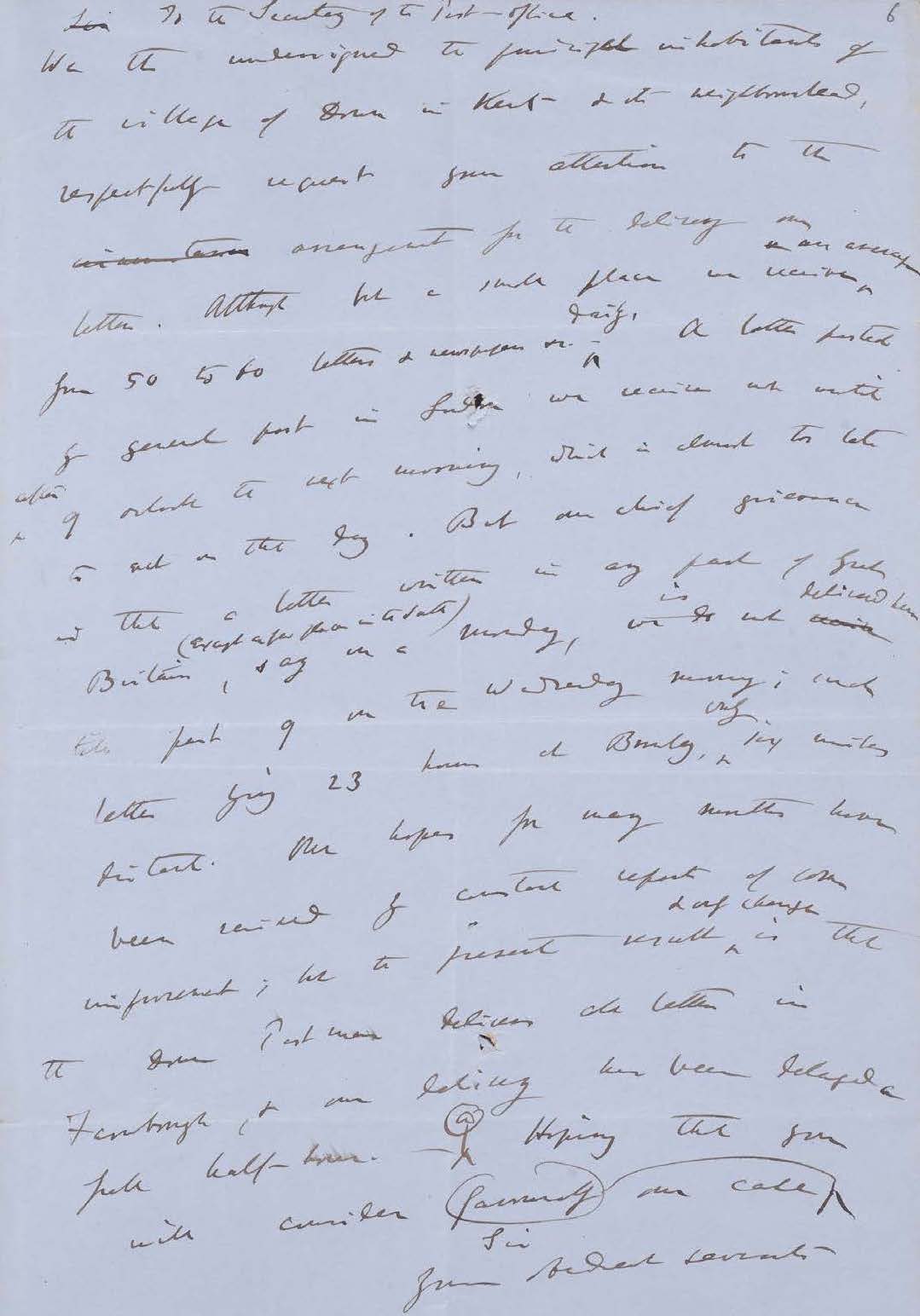

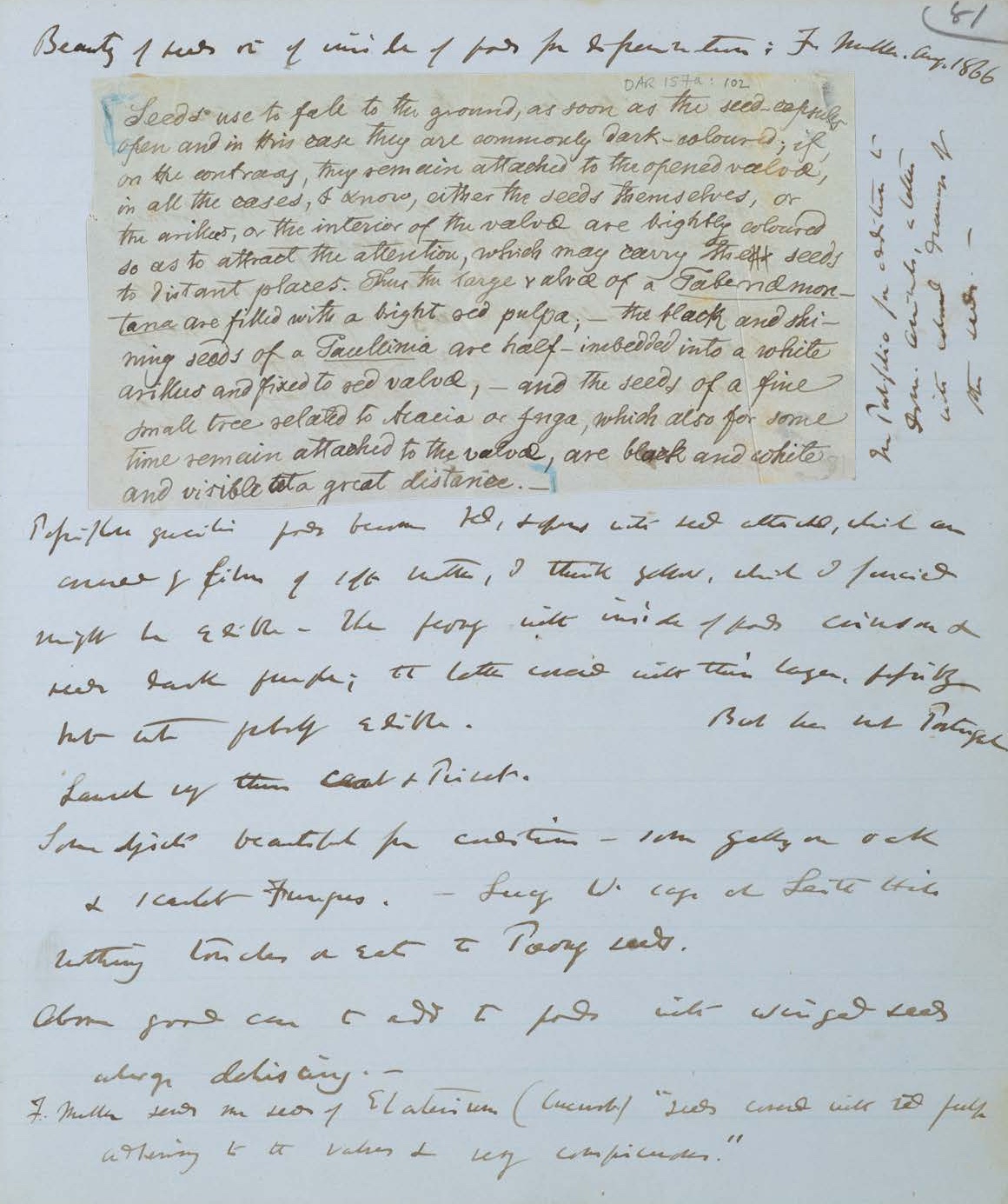

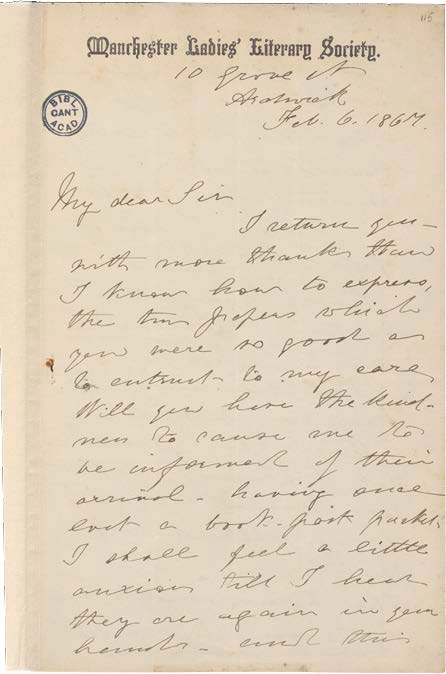

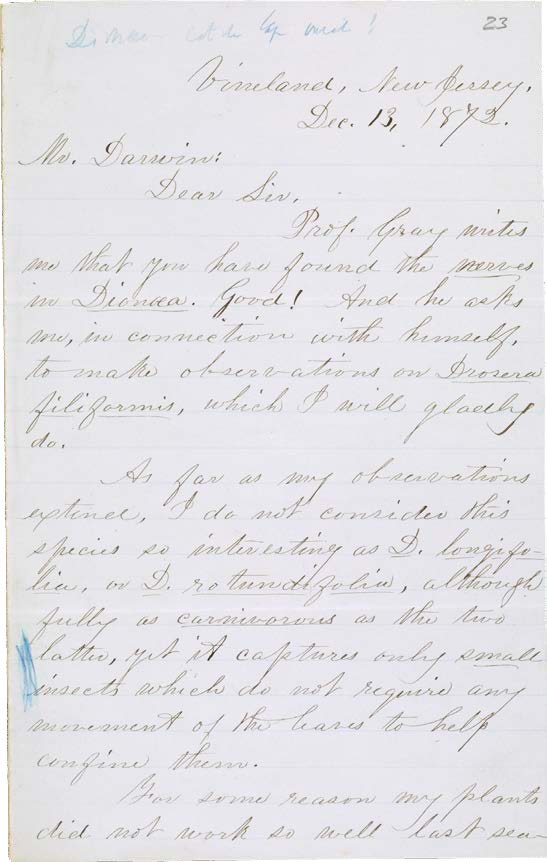

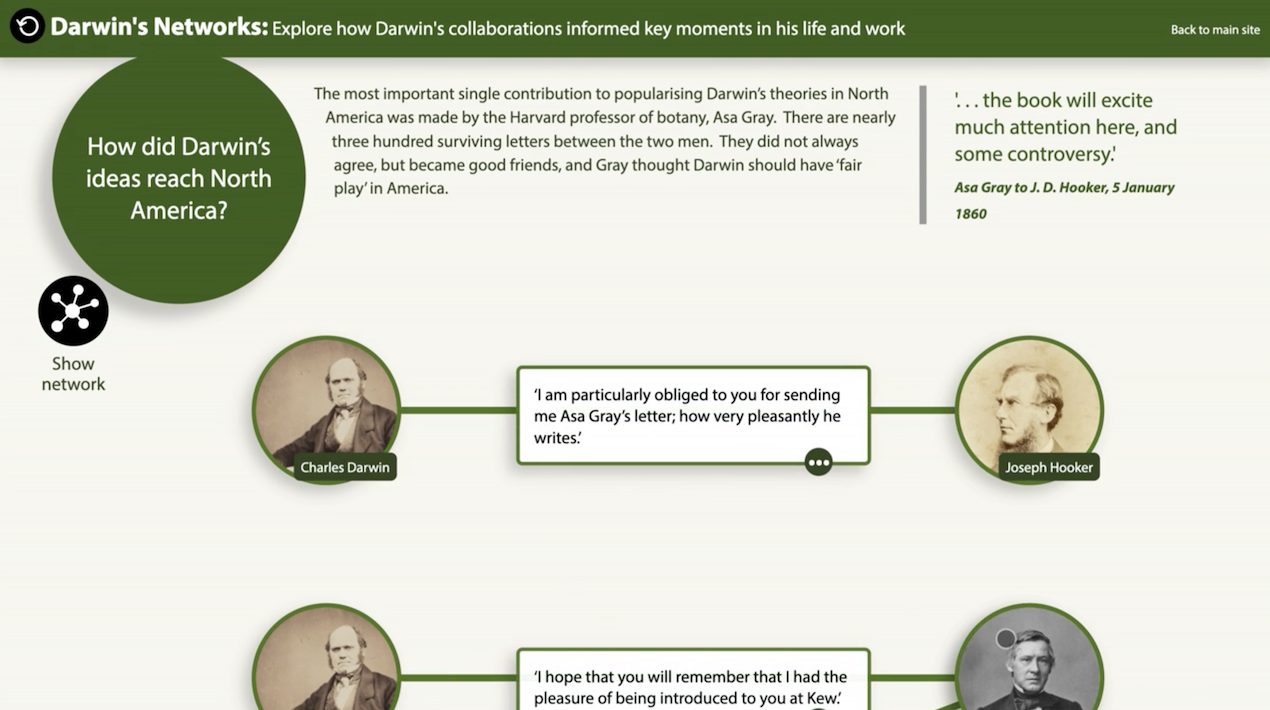

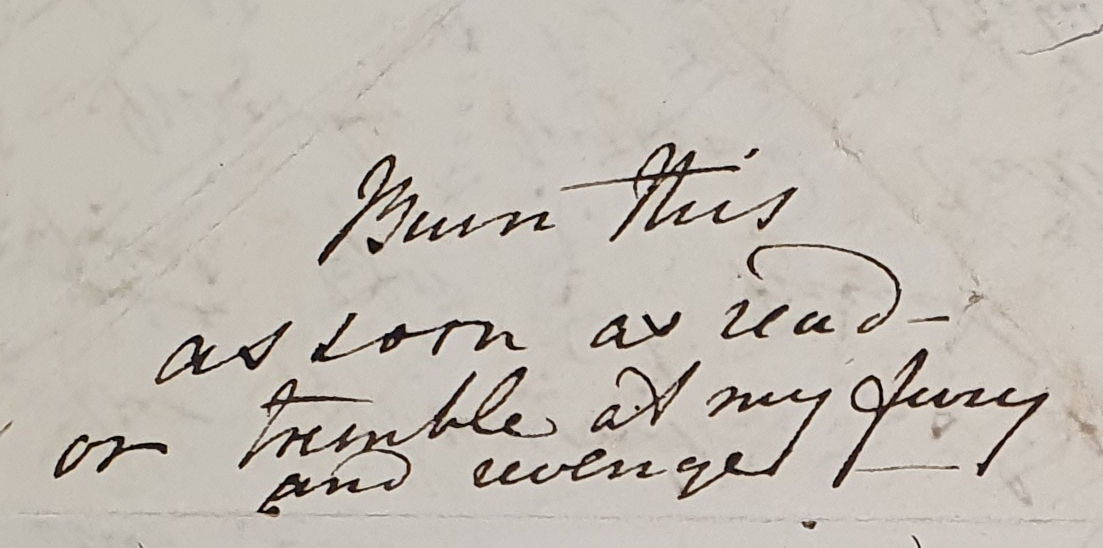

Darwin's letters are a fascinating series of interwoven conversations with his many hundreds of correspondents around the world. This exhibition opens up his life and thought through this intimate medium, and also the lives and thinking of all those women and men with whom he corresponded.

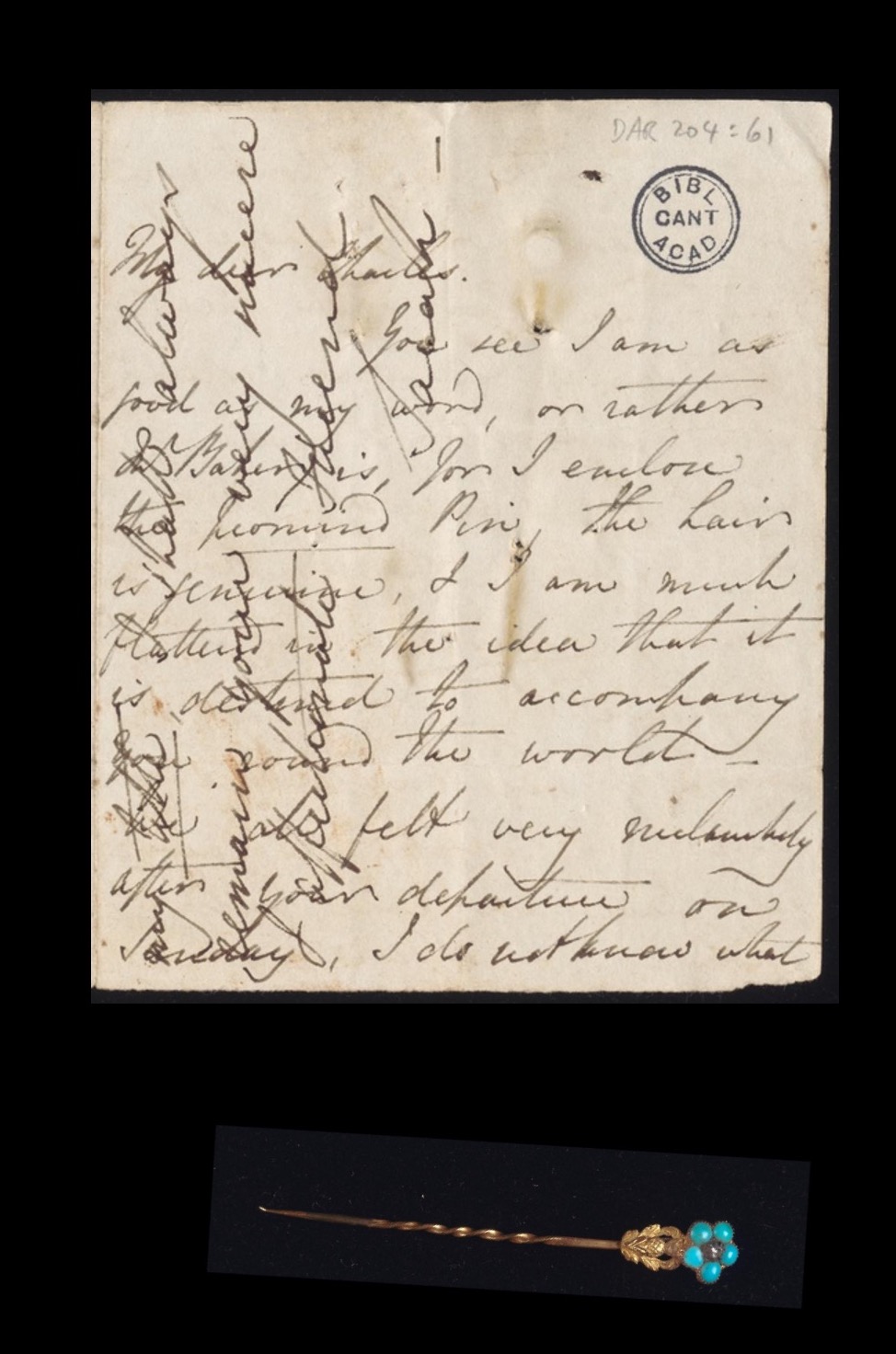

Explore the Beagle voyage through the eyes of the unknown 22-year-old setting out to 'do something' in natural history. He carried with him a letter from a young woman who enclosed not only a jewelled forget-me-not pin but a lock of hair. The letter and pin are on display (sadly the hair does not survive!).

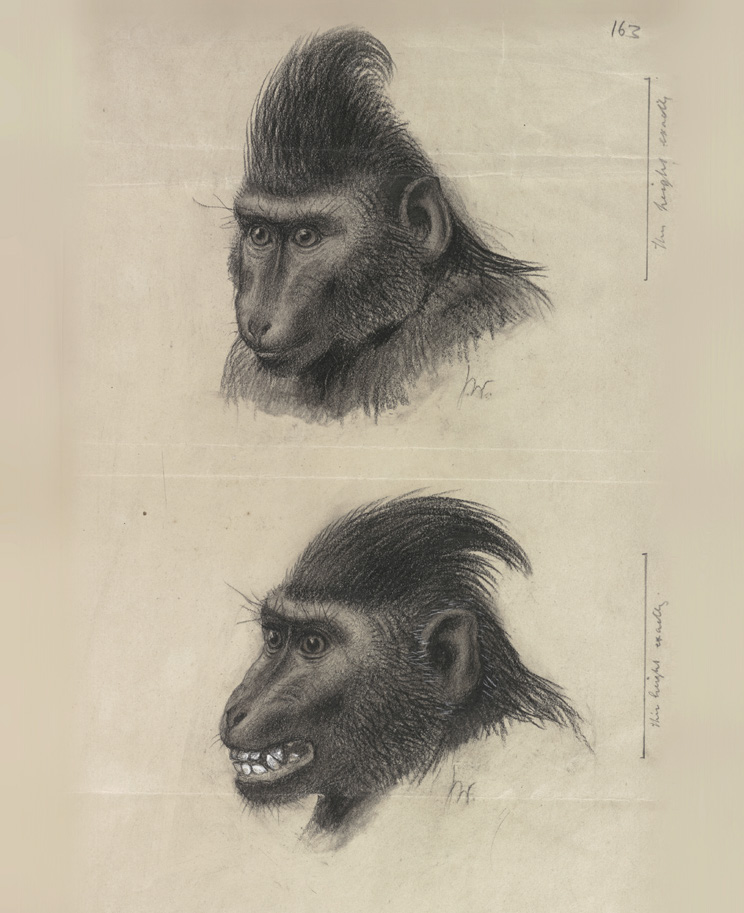

See Darwin's working copies of successive editions of On the Origin of Species. He revised the text in response to new information and criticism, much of it traced to letters.

Letters sometimes came with objects. On display are plant specimens, feathers, photographs, a watercolour of an exotic orchid - even beans sent to Darwin by a market gardener.

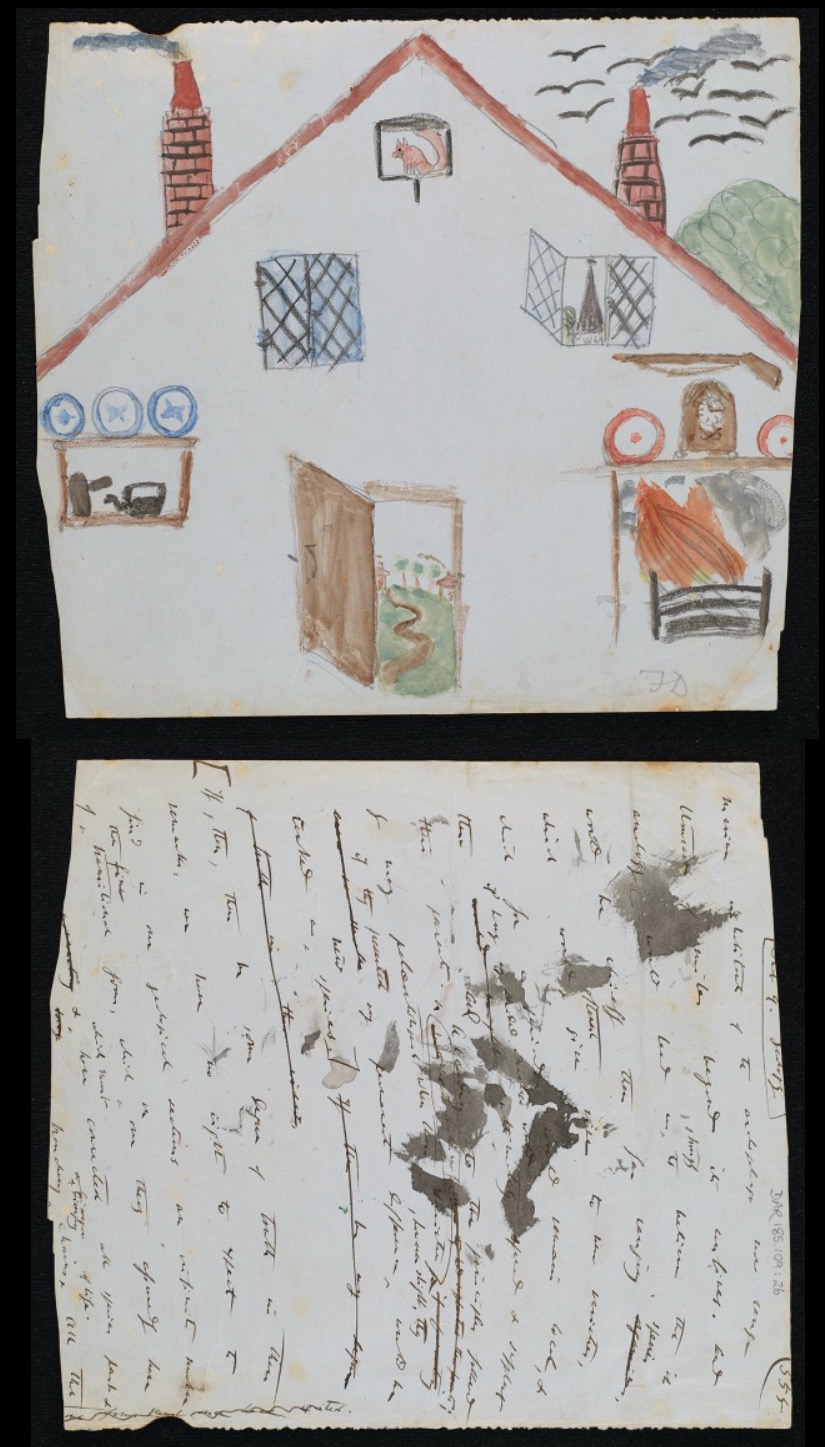

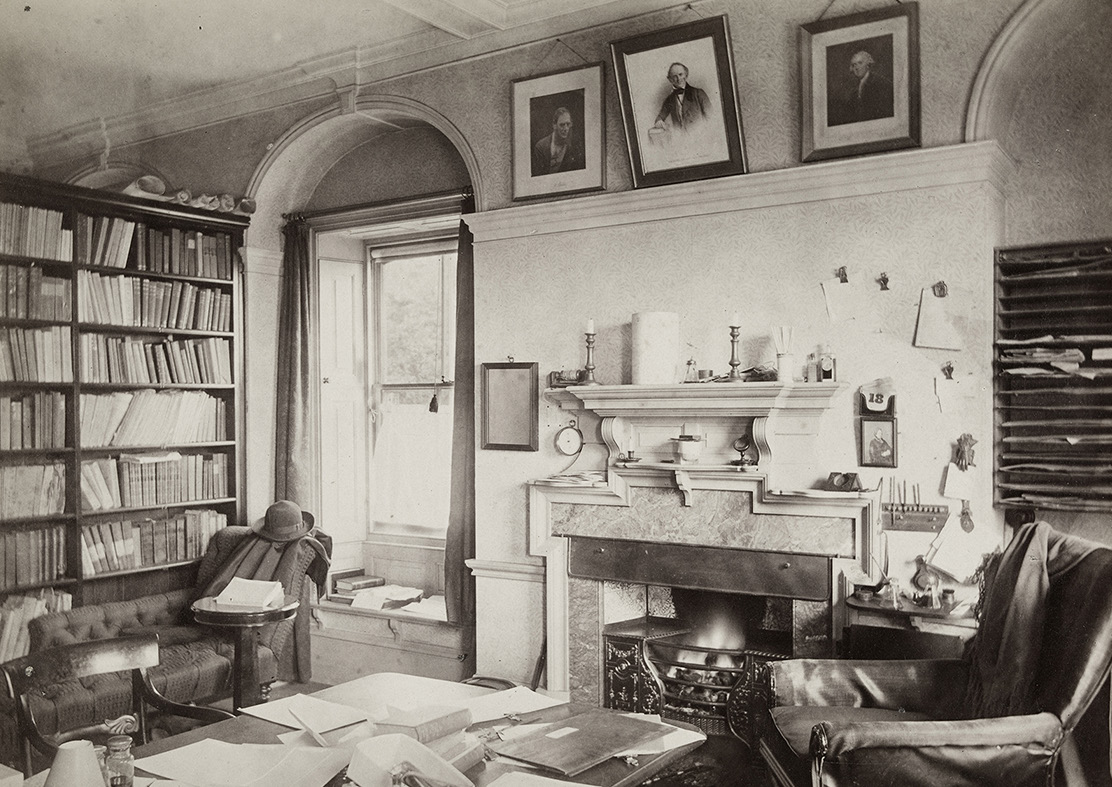

Find out about Darwin's experience of 'Working from home'. For forty years he worked in his study and garden, surrounded not only by letters and specimens but by a large family. As they grew, his children went from being the occasional objects of study to being his assistants. They made observations, edited and illustrated his books, and helped to design experiments and equipment.

Darwin in Conversation

Download the PDF exhibition guide

Download a PDF of transcripts of all the letters featured in the exhibition

Darwin's Species Notebooks

Learn more about the significance of Darwin's iconic 'tree of life' sketch

Explore More

Discover life aboard the Beagle

Find out how Darwin worked from home in his study and garden

Explore Origin in North America

Read about Darwin's first girlfriend

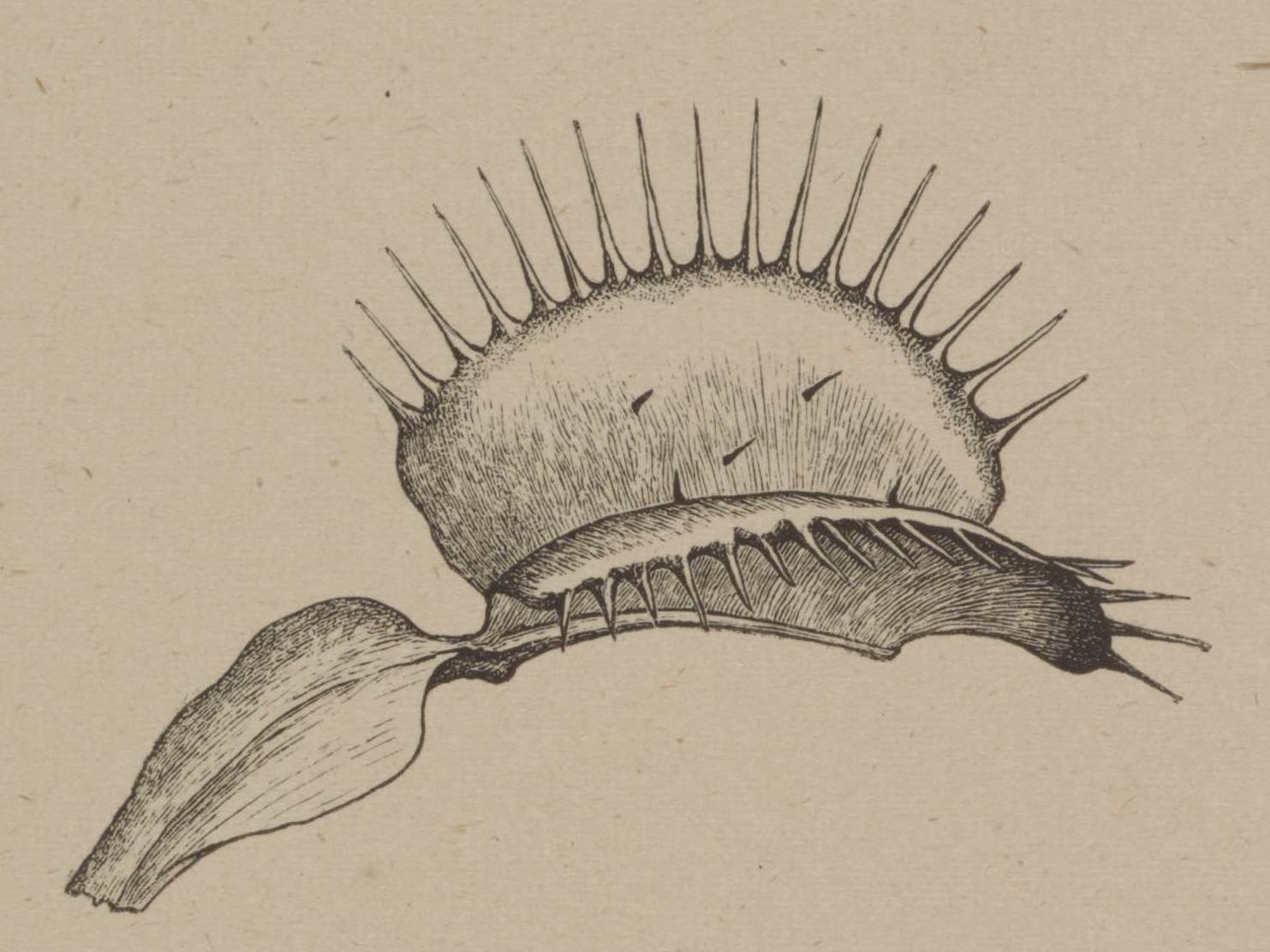

Hear a song about Insectivorous plants

Learn about the strange things Darwin was sent through post

Discover what it was like to visit Down House

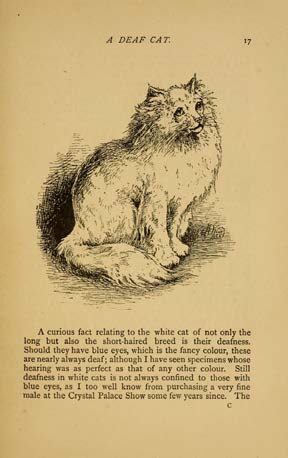

Find out how Darwin changed his mind about cats in subsequent editions of Origin