One of the real pleasures afforded in reading Charles Darwin's correspondence is the discovery of areas of research on which he never published, but which interested him deeply. We can gain many insights about Darwin's research methods by following these 'letter trails' and observing how correspondence served as a vital research tool for him.

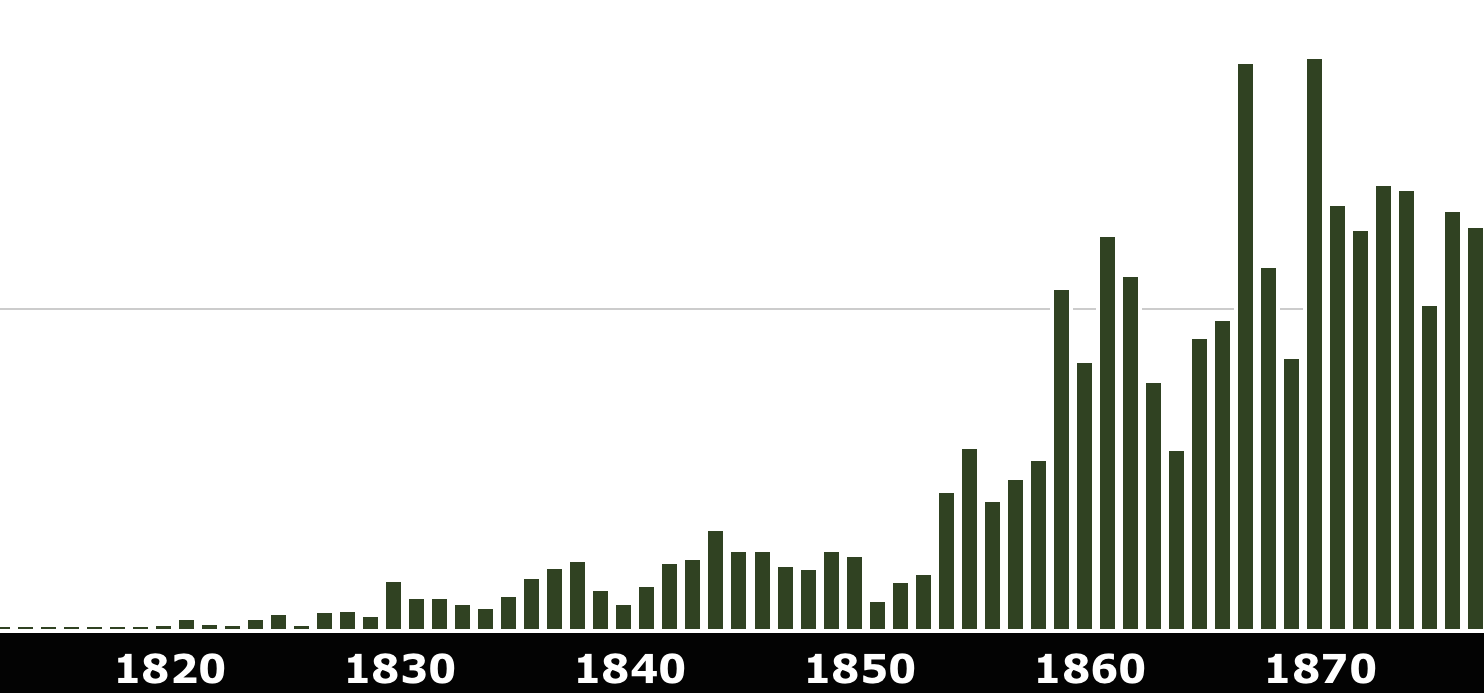

One such story begins with the preparation of a new edition of On the Origin of Species (the fourth) in 1866. Darwin made substantive changes to every new edition of Origin; often the changes were inspired by recent criticism or new research. In 1865, George Douglas Campbell, the eighth duke of Argyll, had written an article that appeared in parts in the magazine Good Words entitled the 'Reign of law'. The article contained an argument about beauty in nature.

The duke, who was best known for his interest in geology and ornithology, claimed:

Spangles of the emerald are no better in the battle of life than spangles of the ruby. A crest of flame does not enable a Humming Bird to reach the curious recesses of an orchid better than a crest of sapphire. … The evidence is indeed abundant, that ornament and variety are provided for in nature for themselves and by themselves, separate from all other use whatever. Any theory on the origin of species which is too narrow to hold this fact, must be taken back for enlargement and repair.

Reign of Law, p. 231.

Campbell's was only the latest statement of a common argument against Darwin's theory, one he had dealt with already in Origin but which he now felt compelled to expand on as he prepared a fourth edition of the book.

Darwin began with the argument that 'the idea of the beauty of any particular object obviously depends on the mind of man, irrespective of any real quality in the admired object; and that the idea is not an innate and unalterable element in the mind,' and continued, 'On the view of beautiful objects having been created for man's gratification, it ought to be shown that there was less beauty on the face of the earth before man appeared than since he came on the stage. Were the beautiful volute and cone shells of the Eocene epoch, and the gracefully sculptured ammonites of the Secondary period, created that man might ages afterwards admire them in his cabinet?'

After mentioning sexual selection as another instance of beauty-with-a-purpose, Darwin turned to the plant world and remarked:

that the gaily-coloured fruit of the spindle-wood tree and the scarlet berries of the holly are beautiful objects, will be admitted by every one. But this beauty serves merely as a guide to birds and beasts, that the fruit may be devoured and the seeds thus disseminated: I infer that this is the case from having as yet found in every instance that seeds, which are embedded within a fruit of any kind, that is within a fleshy or pulpy envelope, if it be coloured of any brilliant tint, or merely rendered conspicuous by being coloured white or black, are always disseminated by being first devoured.

Origin, 4th ed., p. 240.

… or are they?

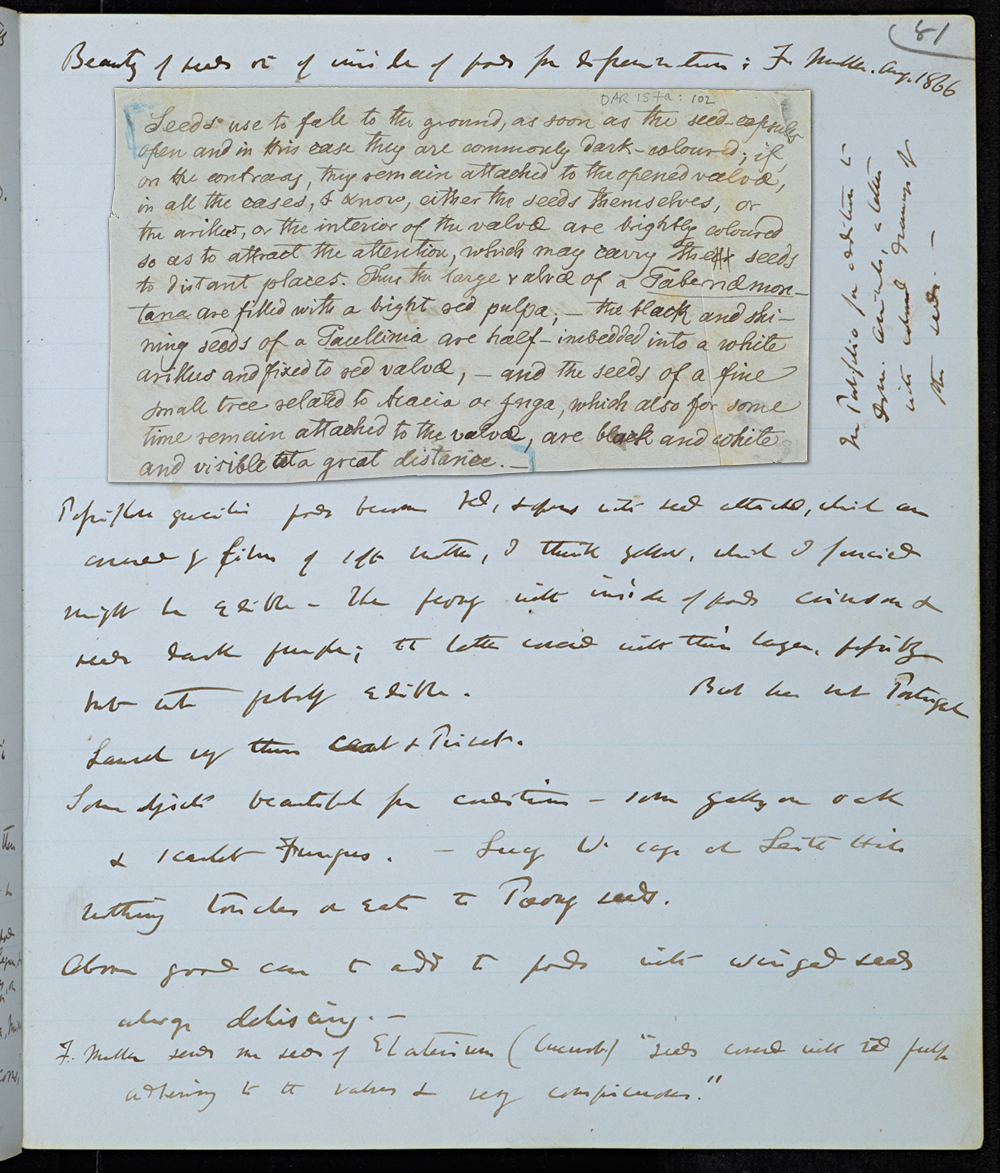

Towards the end of September 1866 Darwin received a letter from Fritz Müller, a German naturalist who had emigrated to Brazil in 1852, and who had begun to correspond with Darwin only a year earlier. The letter is now incomplete; Darwin had pasted one fragment of it into his experimental notebook for reference.

What interested Darwin so much was something that had been on his mind since writing that 'in every instance' seeds were surrounded by a fleshy pulp and 'always disseminated by being first devoured'. Müller had noted that seeds that fell to the ground as soon as the capsule opened were commonly dark-coloured, but those that remained attached to the valve were brightly coloured - or had brightly coloured surrounds - to attract attention.

Seeds use to fall to the ground, as soon as the seed-capsules open and in this case they are commonly dark-coloured; if on the contrary, they remain attached to the open valvæ, in all the cases, I know, either the seeds themselves, or the arillus, or the interior of the valvæ are brightly coloured so as to attract the attention, which may carry the seeds to distant places. Thus the large valvæ of aTabernaemontana are filled with a bright red pulpa;-the black and shining seeds of a Paullinia are half-imbedded into a white arillus and fixed to red valvæ,-and the seeds of a fine small tree related to Acacia or Inga, which also for some time remain attached to the valvæ, are black and white and visible at a great distance.-

Fritz Müller to Charles Darwin, 2 Aug 1866.

Darwin immediately responded:

I have been much interested by what you say on seeds which adhere to the valves being rendered conspicuous: you will see in the new Edit. of the origin why I have alluded to the beauty & bright colours of fruit; after writing this, it troubled me that I remembered to have seen brilliantly coloured seed, & your view occurred to me. There is a species of Peony in which the inside of the pod is crimson & the seeds dark purple. I had asked a friend to send me some of these seeds, to see if they were covered with any thing which cd prove attractive to birds. I recd some seeds the day after receiving your letter; & I must own that the fleshy covering is so thin that I can hardly believe it wd lead birds to devour them; & so it was in an analogous case with Passiflora gracilis. How is this in the cases mentioned by you? The whole case seems to me rather a striking one.

Darwin, C. R. to Müller, J. F. T., 25 Sept [1866]

This letter must have crossed in the post with a follow-up one from Müller (see the letter), who had found more examples of the phenomenon including 'a tree, probably belonging to the Mimoseae, which after the opening of the seed-capsules presents a truly magnificent aspect, being covered over and over with large and elegant curls of pale yellowish silk, (the spirally contracted valves) beset with brilliant red pearls. By the time he received Darwin's letter he had found yet more examples and speculated, 'With Mimosa and Rhynchosia there is no fleshy hull but the seeds are exceptionally hard and since gallinaceous birds often swallow small stones in order to promote the breaking up of their food, I imagined that these hard and conspicuous seeds could well serve the same purpose when swallowed by our Jacús (Penelope) or other birds.' (see the letter) By this time Darwin had already sent some of the seeds Müller had enclosed with his October letter to his best friend, the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, for identification (see the letter).

The selection of seeds in the adjacent photograph will give you some idea of the difficulties.

The selection of seeds in the adjacent photograph will give you some idea of the difficulties.

Darwin picked up on Müller's suggestion and tried the experiment himself, but the results were disappointing. He wrote to Hooker:

I enclose 3 seeds of the Mimoseous tree, of which the pods open & wind spirally outwards & display a lining like yellow silk, studded with these crimson seeds, & looking gorgeous. I gave two seeds to a confounded old cock, but his gizzard ground them up; at least I cd. not find them during 48o in his excrement. Please Mr. Deputy-Wriggler explain to me why these seeds & pods, hang long & look gorgeous, if Birds only grind up the seeds, for I do not suppose they can be covered with any pulp.- Can they be disseminated like acorns merely by birds accidentally dropping them. The case is a sore puzzle to me.-

Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 10 Dec [1866]

Hooker replied with his own speculations:

The Scarlet seed is that of Adenanthera pavonina a native of India. I am well acquainted with itself … I should suppose that it is to imitate a scarlet insect & thus attract insectivorous birds, or frugiferous perchers, of weak digestions, that the color is acquired. The plant is a very common Indian one, & it would be easy to ascertain how far it is a prey to birds.

Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., 14 Dec 1866

Darwin was skeptical about the 'weak gizzard' explanation and although he told Hooker 'it is not worth enquiring in India about, though it is a perplexing case, for I can hardly admit your wriggle of the seeds being devoured by birds with weak gizzards:' he did mention the case to a correspondent in India, John Scott, who duly experimented and replied in September 1867 that his sulphur-crested cockatoo (the cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea is native to Sulawesi and many of the surrounding islands, where Adenanthera pavonina is also found) could 'with little difficulty split their hard testa, and eat with seeming gusto the embryonic parts only rejecting the coloured covering.' It was not surprising that a seed predator would be attracted but where was the benefit to the plant? Scott noted that his cockatoo dropped about half the seeds he tried to eat, possibly confirming Darwin's suggestion of accidental dissemination. But at this point the investigation was finally dropped - and we suppose remained a 'sore puzzle' to Darwin.

So what now?

Luckily for us, modern researchers have taken up the puzzle and have been able to resolve some of the questions Darwin posed. Brazilian ecologist, and former Cambridge PhD student, Mauro Galetti of the Conservation Biology Laboratory at Universidade Estadual Paulista in Rio Claro, Brazil, can bring us up to date on modern research into 'mimetic fruit', as these seeds are now known.

Some plant species have evolved fruits with no nutritive rewards - they enjoy the benefit of dispersal without the cost of pulp production. But how do they get away with it? 'One strategy is to hide small fruits and seeds among leaves that are ingested by large herbivores …. Another strategy is to display colourful seeds resembling fleshy ornithochoric (i.e. bird-dispersed) fruits, so-called "mimetic fruits".' (Galetti 2002, p. 177.)

Like Darwin, Galetti tested seeds on captive birds, and even used guans (the bird species suggested by Fritz Müller) and toucans, but was also able to observe the behaviour of birds and some mammals in the field. Seeds of Ormosia arborea were fed to both granivorous birds with muscular gizzards like guans and frugivorous birds with non-muscular gizzards like toucans. Naïve toucans (captive born) eat more Ormosia than wild captured toucans, a behaviour that might explain how these seeds get dispersed. Afterwards the defecated or regurgitated seeds were planted to observe germination. The surprise was that defacated seeds had much lower rates of germination than those in the control group and so the hypothesis that the seeds might be used as grit by galliform birds was rejected. Another possibility considered was that the seeds were aposematic (colour serves as a warning to seed predators of poison). Although this was provisionally rejected because agoutis (a kind of large rodent) prey on seeds, further study is being done. The hypothesis which best fitted the group's observations was that these seeds are parasitic, that is they deceive naïve birds by mimicking similar-looking fleshy fruits. Galetti listed dozen of species (many of them cited by Darwin and Müller), as mimetic fruits are found in several plant families and this dispersal strategy has evolved independently several times.

Pijl, Leendert van der (1903-90). Dutch botanist. Wrote Principles of dispersal in higher plants (1969; 2nd ed. 1972, 3rd ed. 1982).

- Cazetta, E., Schaefer, H, M., Galetti, M. 2008. Does attraction to frugivores or defense against pathogens shape fruit pulp composition? Oecologia 155: 277-86

- Galetti, M. 2002. Seed dispersal of mimetic seeds: parasitism, mutualism, aposematism or exaptation? In Seed dispersal and frugivory: ecology, evolution and conservation, edited by D. Levey, et al. New York: CABI Publishing.

- Guimaraes Jr., P. R., Galetti, M., Jordano, P. 2008 Seed Dispersal Anachronisms: Rethinking the Fruits Extinct Megafauna Ate, PLoS ONE 3(3): e1745. (Alternative link)