From Edward Blyth 19 February 1867

Feby. 19th. 1867—

My Dear Sir,

I am very sorry to hear of your indisposition, which has disappointed me of the pleasure of meeting you.1 I have been much interested with the 4th. edition of your ‘Origin of Species’,2 & have just been penning a few remarks which occurred to me, which I intended to place in your hands. As it is, I send them to you; but fear that you will regard some of them as a little fanciful.

Yours very Sincerely, | E. Blyth

[Enclosure]

Memoranda for Mr. Darwin—

N.B. The paging refers to the 4th. edit. of “Origin of Species”.

About mocking (p. 506).3 Among mammalia there is one very striking instance in the case of certain Malayan Squirrels (Rhinosciurus of Gray), which wonderfully mimic the appearance of the Tupaiæ among the Insectivora, which inhabit the same region. Size, form (elongated muzzle), colour, character of fur, flattened brush, and even the pale humeral line which is characteristic of the Tupayes, but found in no other Squirrel that I know of.4 I do not, however, perceive the object in this case of mimicry—

Wallace’s instance in the bird class is an extremely remarkable one,5 but several others occur to me. The most familiar to most ornithologists will be that of certain cuckoos (Hierococcyx), the plumage of which is exceedingly Hawk-like both in its immature and adult phases. There are 5 or 6 races of them, all peculiar to the Indian region;6 but though they approximate certain Sparrow-hawks in appearance, the most striking resemblance is with sundry southern hemisphere species allied to Pernis, but which are more widely distributed, as Cymindis uncinatus and C. magnirostris in S. America, Baza cuculoides in S. Africa and B. Reinwardtii and other species in the Malay countries, Celebes, and Australia; to the former of which they can bear no especial reference.7 Even our common cuckoo has somewhat of a hawk-like aspect

A very remarkable instance of apparent mimicry occurs in certain other true cuckoos (Surniculus Dicruroides and S. lugubris), which bear an extraordinary resemblance to the Drongos or ‘King Crows’ (Dicrurus), both in immature and adult plumage;8 & probably they lay their eggs in the Drongos’ nests, but this has not been ascertained.

Certain Doves, as several of the Macropygiæ, are also remarkably cuculine in appearance, but with what object is not very manifest. Also, some of the Graucalus and Campephaga series are very Cuculus-like.9

The Haliaëtus blagrus, which feeds chiefly on sea snakes, is remarkably gull-like, as I have thought when seeing it skim over the waves—pure white with ashy mantle; but Gulls are rare in the Indian Ocean, where indeed there are no species of large size. The great H. pelagicus also strikingly reminds one of the large black-backed Gull.10 There is a striking similarity in the barking voice of the larger Gulls and most of the Sea eagles.

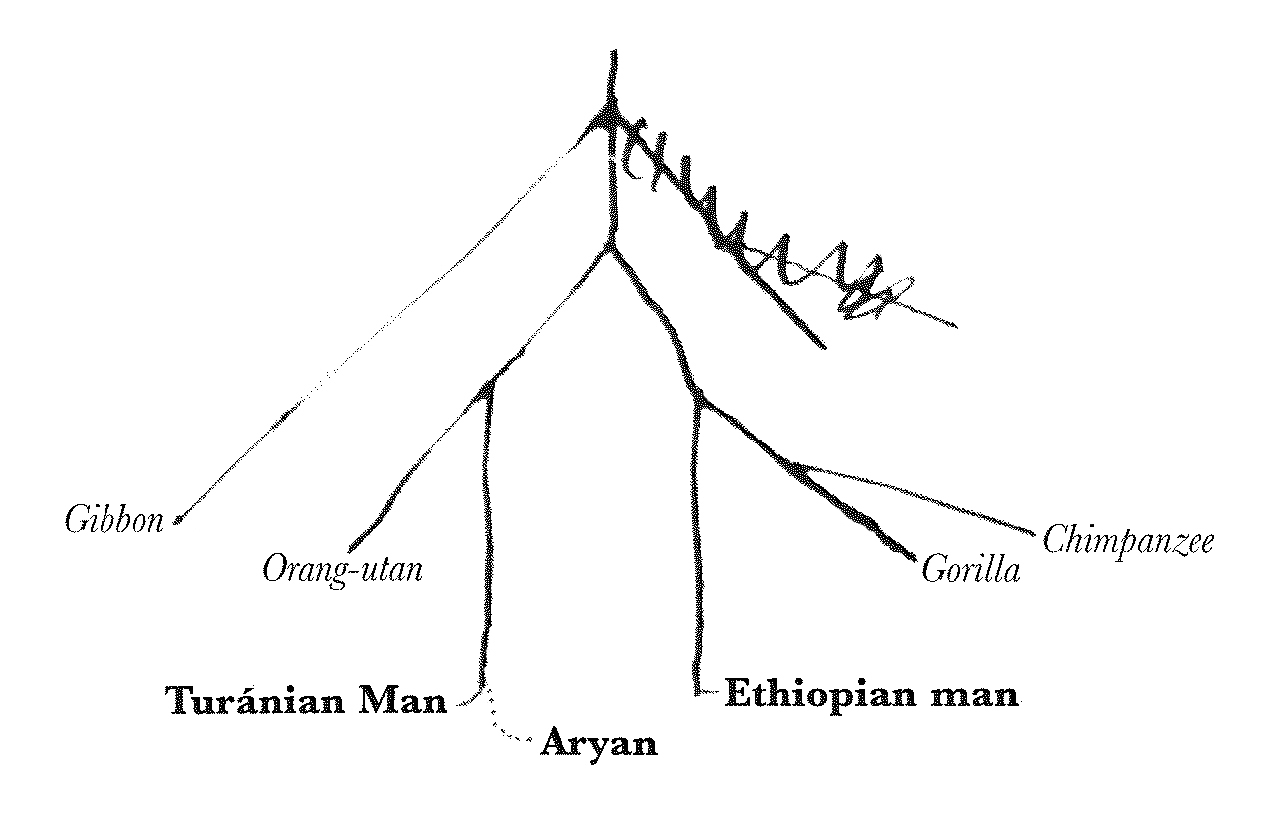

The marked resemblance in facial expression of the Orang-utan to the human Malay of its native region, as that of the Gorilla to the Negro, is most striking, & what does this mean? Unless a divergence of the anthropoid type prior to the specialization of the human peculiarities, which however would imply a parallel series of at least two primary lines of human descent which seems hardly probable; & moreover we must bear in mind the singular facial resemblance of the Lagothrix Humboldtii (a platyrrhine form) to the negro, wherein the resemblance can hardly be other than accidental.11 The accompanying diagram will illustrate what I suggest (rather than maintain); & about Hylobates or Gibbons, I am not sure that I place it right, for, upon the whole, the Gibbons approximate Chimpanzee more than they do the Orang-utan, notwithstanding geographical position. Aryan I believe to be improved Turánian or Mongol—12

To appreciate the likeness of a Malay to an Orangutan, you should see an old Malay women chewing pâu, & note the mobility of the lips, in additional to the general expression. However to be explained, the likeness is much less decided in other races of the grand Turánian stock. We cannot call this a case of mimicry.

I find that the leaf-nosed bats of America are emphatically platyrhine while those of the Old World are catarrhine, & the pteropodine bats are strepsirhine, like the Lemuridæ.13 The genus Taphozous bears a corresponding resemblance to Galæopithicus.14 The facial expression (or physiognomy) of the larger species of Hipposideros recals to mind that of the Orang-utan; and the ordinary bats with simple stomach and cheek-pouches remind us of the Baboon & Macacus series.15 Can we soundly interpret these resemblances, which in the cases first mentioned correspond with geographical distribution? Is there not a significant analogy between the prominent cheek-callosities of the adult male Orang-utan and the facial membranes of the horse-shoe bats?16 I would hardly like to suggest all this in print but it may be thought over.

If different genera of Cheiroptera adumbrate corresponding genera of Quadrumana, so also it may be thought that some genera of Insectivora forecast some of Carnivora; as Tupaia-Herpestes; Potamagale-Lutra; just plausibly indicating different lines of ascent from the lower order to the higher.17 May not the Bruta (i.e. Edentata and Cetacea) descend more directly from Monotremata and other placental mammalia from Marsupialia?

About parasitic cuckoos (p. 259).18 The American Coccyzi are in the condition of the Screech-owls, in having eggs and young of different ages in the same nest.19 Very closely allied to them are the Old World crested cuckoos (Coccystes), which are parasitic, and lay their eggs in the nests of birds about their own size or larger, as C. glandarius in those of magpies and crows.20 Eudynamis orientalis constantly in those of Crows, and the eggs are very similarly marked to those of the Corvi; while those of Coccystes jacobinus are greenish-blue, and are deposited in the nests of the Malacocerci which also produce blue eggs, coloured like those of Accentor modularis. Note well that parasitic Eudynamis is not migratory; and that the eggs of the parasitic Coccystes, as of Coccyzus, are of fair proportionate size; as are also those of the parasitic Molothrus!21 I suspect that Gould is right about the newly hatched cuckoo starving its companions, & so causing their carcases to be removed by the proprietors of the nest. Still it seems wrong to reject the personal observations of Jenner, as you seem to admit in p 291.22

About the origin of dogs (p. 19), consult J. K. Lords work on the Nat. Hist. of British Columbia, for very interesting observations on the derivation of the aboriginal dog of that region from the Canis latrans (which he considers as identical with the Mexican coyote, though Gray separates them. Both are thorough forms of Jackal).23 In Ld Milton & Dr. Cheadles “Journey across North America” are some remarks on the similarity of the sleigh dogs to wolves; & see also Paget’s Travels in Hungary & Transylvania.24

If the different-sized races of European or humpless cattle derive from different wild races, as primigenius, frontosus, longifrons, & trachoceros, we should suspect the same of the still more contrasted races of domestic humped cattle, which also probably descend from more than one wild original. N.B. “Bráhmini cattle” is a misnomer. Any bull dedicated to Bráhma becomes a “Bráhmini bull”, and the latter are generally of the smaller races so far as I have seen. I think it probable that there have been different wild races of the Zebu form, as likewise of the humpless taurines?25

P. 281. A nuthatch does not hammer downwards at an object, like a titmouse, or a nutcracker (Nucifraga), but delivers the blow forward with a swing of the body, if I mistake not; so different an action that one is not likely to pass into the other. I can hardly imagine a titmouse striking in the manner of a nuthatch!26

P. 417. Recent observations have shewn that there is a much greater community of species than was supposed on the two sides of the Isthmus of Panamá; on which subject consult Günther.27 The absence of corals on the western side is believed to be due to the existence of a cold current, as of course you know.

p. 556. Those curious South American birds, the Palamedea and Chauna, are most closely allied to the spur-winged geese of Africa (Plectropterus), and in reality, are true Anatidæ, though not web-footed; in the semi-palmate geese of Australia (anseranas melanoleuca), there is a decided approach in the shape of the bill to the screamers; and I cannot think how any naturalist can look at a living Palamedea without perceiving at once that it is non-palmate goose!28 A. Newton29 agrees with me in this opinion. The Parra group is quite distinct, & its affinity is with the snipe and plover series, & not at all with the Rallidæ, Anatomy, plumage, eggs, chicks, &c &c.30

P. 13 Have you ever examined the additional toe so constant in the Dorking fowls, as also in the Chinese Shang-hai bird?31 How many phalanges has it? A sixth finger or toe is exceedingly apt to be transmitted by generation in human beings, but being taken off soon after birth, & the fact kept secret, we do not generally hear of it; though I have heard of some remarkable instances, wherein almost every child of a large family has inherited this redundancy.32

For the highly predatory and carnivorous habits of the Weka Rail of New Zealand (Ocydromus australis), vide ‘Ibis’, 1862, p. 103.33 Some of the New Zealand birds seem hardly to have yet acquired sufficient distrust of man (ibid. p. 105–6), as Petroica alighting on the hand, and Carpophaga allowing to have a snare be placed on its neck; the latter ascribed to “stupidity”, whereas I should rather say non-experience. The extraordinary familiarity of the Canada jay (Perisoreus canadensis) is worthy of notice. Vide Lord and others.—34 Note diving habits of common Cape Petrel (Daption capensis ibid p. 99).35

CD annotations36

CD note:38

Footnotes

Bibliography

Birds of the world: Handbook of the birds of the world. By Josep del Hoyo et al. 17 vols. Barcelona: Lynx editions. 1991–2013.

Blyth, Edward. 1842–3. A monograph of the Indian and Malayan species of Cuculidæ, or birds of the cuckoo family. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal n.s. 11: 897–928, 1095–112; 12: 240–7.

Blyth, Edward. 1866–7. The ornithology of India. A commentary on Dr. Jerdon’s Birds of India. Ibis n.s. 2 (1866): 225–58, 336–76; 3 (1867): 1–48, 147–85.

Brandon-Jones, Christine. 1995. Long gone and forgotten: reassessing the life and career of Edward Blyth, zoologist. Archives of Natural History 22: 91–5.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Davies, N. B. 2000. Cuckoos, cowbirds and other cheats. London: T & A D Poyser.

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

DNB: Dictionary of national biography. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. 63 vols. and 2 supplements (6 vols.). London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1912. Dictionary of national biography 1912–90. Edited by H. W. C. Davis et al. 9 vols. London: Oxford University Press. 1927–96.

Fleagle, John G. 1999. Primate adaptation and evolution. 2d edition. San Diego: Academic Press.

Gould, Stephen Jay. 1997. The mismeasure of man. Revised and expanded edition. London: Penguin Books.

Graves, Joseph L., Jr. 2002. The emperor’s new clothes; biological theories of race at the millennium. New Brunswick, N.J., and London: Rutgers University Press.

Gray, John Edward. 1843. List of the specimens of Mammalia in the collection of the British Museum. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

Günther, Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf. 1864–6. An account of the fishes of the states of Central America, based on collections made by Capt. J. M. Dow, F. Godman, Esq., and O. Salvin, Esq. [Read 22 March 1864 and 13 December 1866.] Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 6 (1863–7): 377–494.

Jenner, Edward. 1788. Observations on the natural history of the cuckoo. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 78: 219–37.

Journal of researches 2d ed.: Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of HMS Beagle round the world, under the command of Capt. FitzRoy RN. 2d edition, corrected, with additions. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1845.

Layard, Edgar Leopold. 1862. Notes on the sea-birds observed during a voyage in the Antarctic Ocean. Ibis 4: 97–100.

Lord, John Keast. 1866. The naturalist in Vancouver Island and British Columbia. 2 vols. London: Richard Bentley.

Natural selection: Charles Darwin’s Natural selection: being the second part of his big species book written from 1856 to 1858. Edited by R. C. Stauffer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1975.

Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker’s mammals of the world. 6th edition. 2 vols. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

OED: The Oxford English dictionary. Being a corrected re-issue with an introduction, supplement and bibliography of a new English dictionary. Edited by James A. H. Murray, et al. 12 vols. and supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1970. A supplement to the Oxford English dictionary. 4 vols. Edited by R. W. Burchfield. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1972–86. The Oxford English dictionary. 2d edition. 20 vols. Prepared by J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. Oxford English dictionary additional series. 3 vols. Edited by John Simpson et al. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1993–7.

Origin 4th ed.: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 4th edition, with additions and corrections. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1866.

Origin 5th ed.: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 5th edition, with additions and corrections. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1869.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Paget, John. 1839. Hungary and Transylvania; with remarks on their condition, social, political, and economical. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Stanton, William. 1960. The leopard’s spots; scientific attitudes toward race in America 1815–59. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Stocking, George W., Jr. 1982. Race, culture, and evolution: essays in the history of anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stocking, George W., Jr. 1987. Victorian anthropology. New York: The Free Press. London: Collier Macmillan.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

Summary

Encloses memorandum on Origin [1866]

discussing mimicry in mammals and birds,

abnormal habits shown by birds,

behaviour of cuckoos,

and analogies existing between mammals of the same geographical region.

Speculates on possible lines of development linking groups of mammals.

[CD’s notes on the verso of the letter are for his reply.]

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-5405

- From

- Edward Blyth

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- unstated

- Source of text

- DAR 160: 209, 209/1 & 2, DAR 47: 190, 190a, DAR 80: B99–99a, DAR 205.11: 138, DAR 48: A75

- Physical description

- ALS 1p †, encl 5pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 5405,” accessed on 26 September 2022, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-5405.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 15