From G. R. Waterhouse 13 February 1858

British Museum

Feb. 13. 58

My dear Darwin

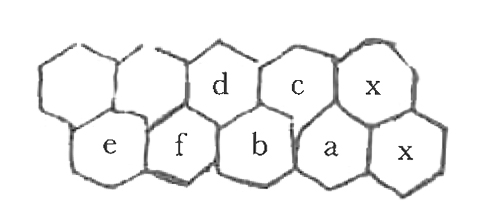

I do very much wish that you could see the Wasp’s nest alluded to by Mr. Smith, and especially some other nests which accompanied it—1 I must own I was startled by it at first—it is composed of ten cells (two rows of 5, arranged side by side, thus:—

They vary much in length, the two to the right marked (x) are perhaps of their full length, and 4 of those on the left are so likewise, but a & b are only about the length of the others; and, c & d, about ds of the length—this irregularity I have never seen before and if we get another nest made by the same insect I have no doubt it would not resemble this— The whole of the cells are hexagonal, the only difference which is noticeable is that the angles are rather less true on the outer sides than on the innersides of the cells, this is more particularly the case in cells e & f.—

They vary much in length, the two to the right marked (x) are perhaps of their full length, and 4 of those on the left are so likewise, but a & b are only about the length of the others; and, c & d, about ds of the length—this irregularity I have never seen before and if we get another nest made by the same insect I have no doubt it would not resemble this— The whole of the cells are hexagonal, the only difference which is noticeable is that the angles are rather less true on the outer sides than on the innersides of the cells, this is more particularly the case in cells e & f.—

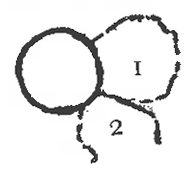

In the same small case with the nest just noticed, which I will call Smith’s

nest, there is the nest of a nearly allied insect (genus Mischocyttarius) It is composed of 3 full

grown cells & one very young one—they are all cylindrical (or rather

conico-cylindrical, for they are rr. smaller

at the base than at the outlet) three of the 4 just touch each

other, the 4 nearly touches but is absolutely free throughout— The

next nearest nest (also of nearly allied insect) is composed of a mass

of 12 to 14 cells—in size & ∠ (I was going to say

form) extremely like the cells of the last mentioned nest.— As you view

this nest from the outside, without seeing the entrances of the cells,

you would believe it to be composed of a number of conico-cylindrical

cells packed closely together—but look at the mouths of the cells, you

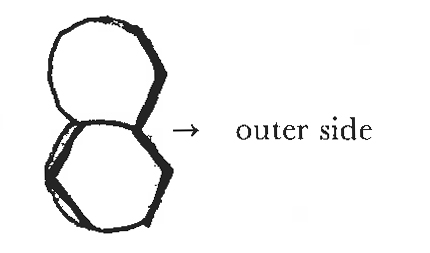

see that all the inner ones are hexagonal the outer ones & — one of the outer cells which comes in unequal contact with

2 other cells is of this form

two of its sides are composed of flat plates, but one plate is

broader than the other, the broad plated side being in contact with more

of the adjoining cell No. 2 than the

narrow plated side with the cell No 3—

two of its sides are composed of flat plates, but one plate is

broader than the other, the broad plated side being in contact with more

of the adjoining cell No. 2 than the

narrow plated side with the cell No 3—

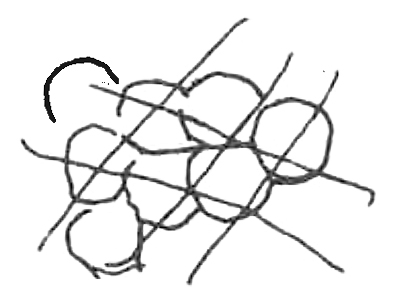

Then we come to a fourth nest (I am taking them just as they stand) and this is made by an insect of the same genus as that which made “Smith’s nest”—viz. the genus Icaria— It is built on a thin piece of stick, & is composed of say 20 or more cells—at first a single cell, & this followed by 2 cells, then 2 more behind these then 3 & so on, the whole mass of cells forming a long narrow comb which, so far as I recollect, presents, at the widest part, about 4 cells abreast— Here are the eight first cells

I made the sketch from my memorandum & no sooner had I done it than I felt sure it was wrong—went to look at the nest, and, as usual, I find the additional cells are built in the interstices of other cells—it should be thus—

These cells are at first rounded where they are not in contact with others and angular where they are in contact, but as they progress they become slightly angular on the free sides—

These cells are at first rounded where they are not in contact with others and angular where they are in contact, but as they progress they become slightly angular on the free sides—

Now for a word or two about the Wasp’s, or Hornet’s nest, for they are the same—& here I shall no doubt trouble you with stuff which I have told you before, but I know not what I have said in our conversations—in print I think I have never given any account of the Wasp’s nest— There then, is this important difference between the wasp’s nest & the Hive Bee’s—viz. that in the latter case as number of insects are at work upon the nest at one and the same time but in the case of the Wasp the first comb, at least, is made by a single female; and, the most important fact connected with my theoretical views as to its structure is this—that the wasp never builds a single, isolated cell.—but begins her work by building parts of many cells and these parts of cells are closely packed together—2

Owen thinks he has altogether smashed my theory by bringing the Wasp’s cell to bear upon it,3 but when a theory is made to explain one thing (the Hive Bee’s nest) and it is found that what has literally been set down, will not explain another thing, I take it, it is but just that I should be entitled to something more than the mere words used in the first case—what can fairly be inferred, & indeed, what almost follows of necessity, is due to me— I take it that the essence of my theory is that the insects in question all work in segments of circles & that the hexagonal cells, may be (theoretically) looked upon as altered cylinders—4 The Hive bee works apparently upon the inner side of the cell, leaving her neighbours to look to the outside— The wasp works at both sides of her cell, and theoretically alters her bit of cylinder as soon it is made, or why is it that the cells of the outermost row of the comb are only angular on the inner side—my answer is she can’t get at the outside of these cells—there’s no room, for the outermost row is nearly in contact with the walls of the nest— There’s another part of the Wasp’s cell that the insect perhaps can’t, or at any rate does not meddle with, & that is the bottoms of the cells—these are hemispherical externally & thus differ from the Hive Bee’s cells— in one case the cells come in contact with other cells at the bottom, & in the other they do not!!— I cannot help, here, putting a question to those who have no faith in my explanations— It is known that if a number of circles of equal size are packed close, side by side, every circle must be surrounded by six others— Now sup-posing such were not the case, & that every circle was surrounded say by 5 other circles—(& here by way of parenthesis I would ask, have you looked well to the cells of the different kinds of Bees & wasps, & especially have you paid attention to the numerous exceptions that occur to the hexagonal form)— Do you think that the cells of Bees &c would be hexagonal, if the supposed case about the circles were a true one—?

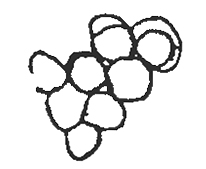

Well I have said that the cells of the outermost row in the completed wasp’s comb are not hexagonal—this is not always the case, I can show you a comb of a Hornet’s nest, (& I regard the Hornet as a Wasp) in which the material of many of the outer cells has been removed or worked upon in such a manner as to give to them a hexagonal form, though less perfect often than the other cells—thus

as these cells were built the insect removed the superfluous material from the interstices, & there are cases in which a cell stands isolated so far the cells which should to the right and left are concerned, these being absent, & though these cells are cylindral towards the base they gradually become hexagonal (the free angles rather rounded) towards the mouth of the cell—5

as these cells were built the insect removed the superfluous material from the interstices, & there are cases in which a cell stands isolated so far the cells which should to the right and left are concerned, these being absent, & though these cells are cylindral towards the base they gradually become hexagonal (the free angles rather rounded) towards the mouth of the cell—5

It is now 4 o’clock & I must send this to the post, for if I do as I did yesterday & the day before leave it until “tomorrow” you will never get it— I couldn’t finish what I had to say when I wrote before6 & I found I had said so much too much for you to read that I have written fresh letters 3 days running— This is the worst as to quantity—

Faithfully Yours | Geo R Waterhouse

Footnotes

Bibliography

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

[Waterhouse, George Robert.] 1835. Bee. In The penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, edited by Charles Knight, vol. 4, pp. 149–56. London: Charles Knight.

Summary

GRW’s observations of and ideas on bees’ and wasps’ cells.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-2216

- From

- George Robert Waterhouse

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- British Museum

- Source of text

- DAR 181: 23

- Physical description

- ALS 11pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 2216,” accessed on 26 September 2022, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-2216.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 7