Cambridge University Library

Darwin's study of barnacles, begun in 1844, took him eight years to complete. The correspondence reveals how his interest in a species found during the Beagle voyage developed into an investigation of the comparative anatomy of other cirripedes and finally a comprehensive taxonomical study of the entire group. Despite struggling with a recurrent illness, he continued to write on geologicy, and published notes on the use of microscopes. Three more children, Elizabeth, Francis, and Leonard, were born during this period, but the death of Darwin's father in 1848 left the family well-provided for.

Read more

|

Emma Darwin with Leonard Darwin as a child

Cambridge University Library

The seven-year period following Darwin's return to England from the Beagle voyage was one of extraordinary activity and productivity in which he became recognised as a naturalist of outstanding ability, as an author and editor, and as a professional man with official responsibilities in several scientific organisations. They are also the years in which he married, started a family, and moved to Down House, Kent, his home for the rest of his life. By 1842 he was ready to write an outline of his species theory, the so-called 'pencil sketch', based on a principle that he called 'natural selection'.

Read more

|

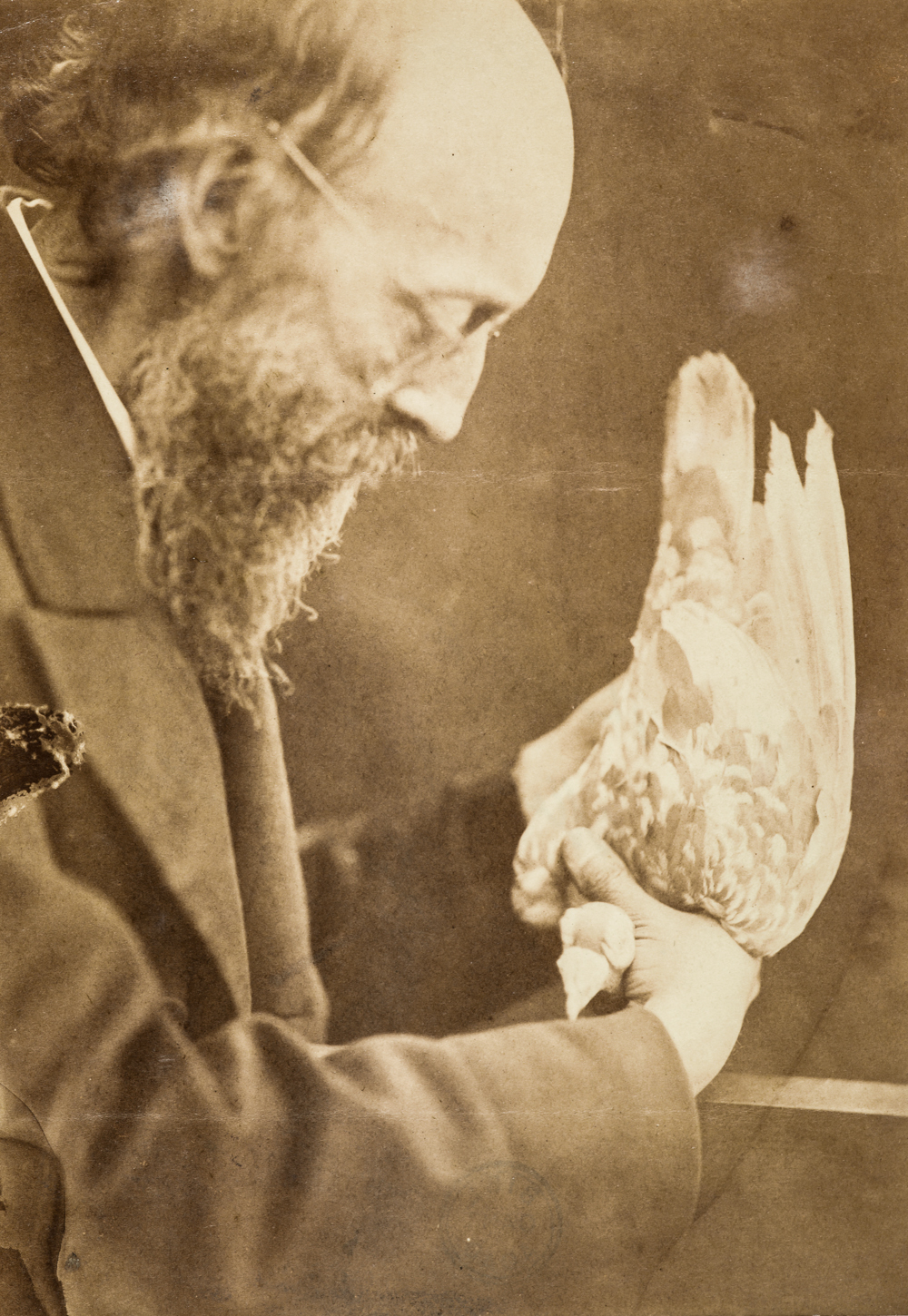

William Bernhard Tegetmeier

Cambridge University Library

In May 1856, Darwin began writing up his 'species sketch' in earnest. During this period, his working life was completely dominated by the preparation of his 'Big Book', which was to be called Natural selection. Using letters are the main source for much of his research he amassed data, carried out breeding experiments, and struggled with statistical analysis. Several of his experiments: seeds would not germinate; beans failed to cross; newly-hatched molluscs refused to do what he hoped. Most significant in terms of Darwin's future, however, was the beginning of his correspondence with Alfred Russel Wallace.

Read more

|