Dr Duchenne and his galvanic probe

About our experiment

Darwin was endlessly curious and we hope to provoke curiosity too. Are there core emotions? What are they and how many? Why do we express emotion in the way we do? How do we recognise it and can we be sure we all mean the same things? Is the expression of emotion innate? Or is it culturally modified? How do we equate different words to describe emotion (even in one language, let alone across different languages)? Can a static image ever convey emotion accurately? How do actors and artists convey it? These are all questions that Darwin was beginning to address and into which there is a great deal of current research. The Darwin Correspondence Project and CAREThave teamed up with researchers at the Cambridge University Computer Laboratory, and with Professor Simon Baron-Cohen. The design of our recreation of Darwin's experiment is based on one used by Peter Robinson's research group in the Cambridge University Computer Laboratory. One of the problems Darwin faced was whether to suggest possible responses to his participants or to allow them to use their own words. Just as Darwin chose to do, we accept any response, but Darwin only had to codify twenty-four responses! Our experiment will be on a much larger scale, so we use a compromise format developed by the Computer Lab to suggest possible answers drawn from their database, using a version of predictive text. But if you don't see what you want, put in something new!

The photographs

Darwin selected the photographs from an original collection of seventy-three made by a French physiologist, Benjamin Amand Duchenne, and published alongside his book, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, ou analyse électro-physiologique de l'expression des passions(Duchenne 1862). Darwin's copy of the book and plates, some with his annotations, are in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University Library (DAR LIB 160).

Image: Duchenne designed this apparatus to stimulate muscles by passing an electric current between electrodes

Duchenne had set out to find the muscles responsible for creating particular expressions using an electrical device he had originally developed to investigate the muscles that control the hand. He applied galvanic probes to the facial muscles of a number of different test subjects. He also took what today could be thought of as control photographs of the same people with blank expressions, and others where they were attempting to simulate expressions without the aid of the probes. Duchenne published photographs of five people, choosing a range of ages: a young girl, a young woman, an older woman, a young man, and an old man. Of these his principal subject was " an old, toothless, man, with a thin face, whose appearance, without being precisely ugly, was more or less nondescript" and whose "intelligence was limited" ("un vieillard édenté, à la face maigre, dont les traits, sans être absolument laids, approchent de la trivialité, … et son intelligence assez bornée." ) His age and leanness meant that the contraction of his muscles produced particularly good wrinkles, but the old man had another advantage from Duchenne's point of view: he suffered from a medical condition that had left him with little feeling in his face. Duchenne had clearly had trouble persuading many people to take part in his experiment as although, he said, the process was not very painful, it caused uncomfortable muscle spasms. Darwin was fascinated by the photographs, and admired Duchenne's achievements, but was sceptical of his claim to have identified individual muscles responsible for the expression of particular emotions. After conducting his experiment Darwin sent Duchenne's whole album of plates to James Crichton-Browne, one of his correspondents, to get another opinion on their accuracy. Crichton-Browne, a doctor who pioneered work on the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness, ran a large mental asylum in Wakefield, Yorkshire, and had supplied Darwin with information on the behaviour and expressions of his patients. Crichton-Browne sent Darwin a detailed critique of several of Duchenne's plates [ read letter ], but not until he had given Darwin a scare by hanging on to the plates so long that Darwin was afraid they had been lost in the post [ read letter].

Darwin's use of the photographs in Expression

Three years after running his experiment, when he was organising the illustrations for his book, Expression, Darwin wrote to Duchenne and got permission to include some of his photographs. He originally intended to have them copied and engraved, but in the end he reproduced two as engravings and a further six as photographs, taking advantage of new photographic printing processes. Of the photographs that Darwin used in Expression, the originals of both of the engravings and two of the other photographs had been used in the experiment, but for both his own experiment and in Expression, Darwin chose photographs of only two of Duchenne's five subjects: the old man, and the young man. According to Duchenne the young man was an anatomist who had an unusual ability to move his eyebrows - he is identifiable elsewhere as Jules Talrich, an anatomical modeller. Although Darwin had shown his visitors a photograph of Talrich with the electrical probes attached, in Expression the probes only appear in two photographs of the old man, who, Darwin was careful to tell his readers "was little sensitive". The engraver was instructed to leave the electrodes out of the two representations of "terror" and "horror and agony".

Darwin used four more of Duchenne's photographs that he had not shown his visitors: Fig. 3 (Expression Plate III, Fig. 4), Duchenne Fig. 4 (Expression Plate II, Fig. 1), Duchenne Fig. 31 (Expression Plate III, Fig. 6), Duchenne Fig. 32 (Expression Plate III, Fig. 5); there are annotations suggesting that he also considered using Duchenne Figs. 44 and 45.

Darwin's guinea pigs

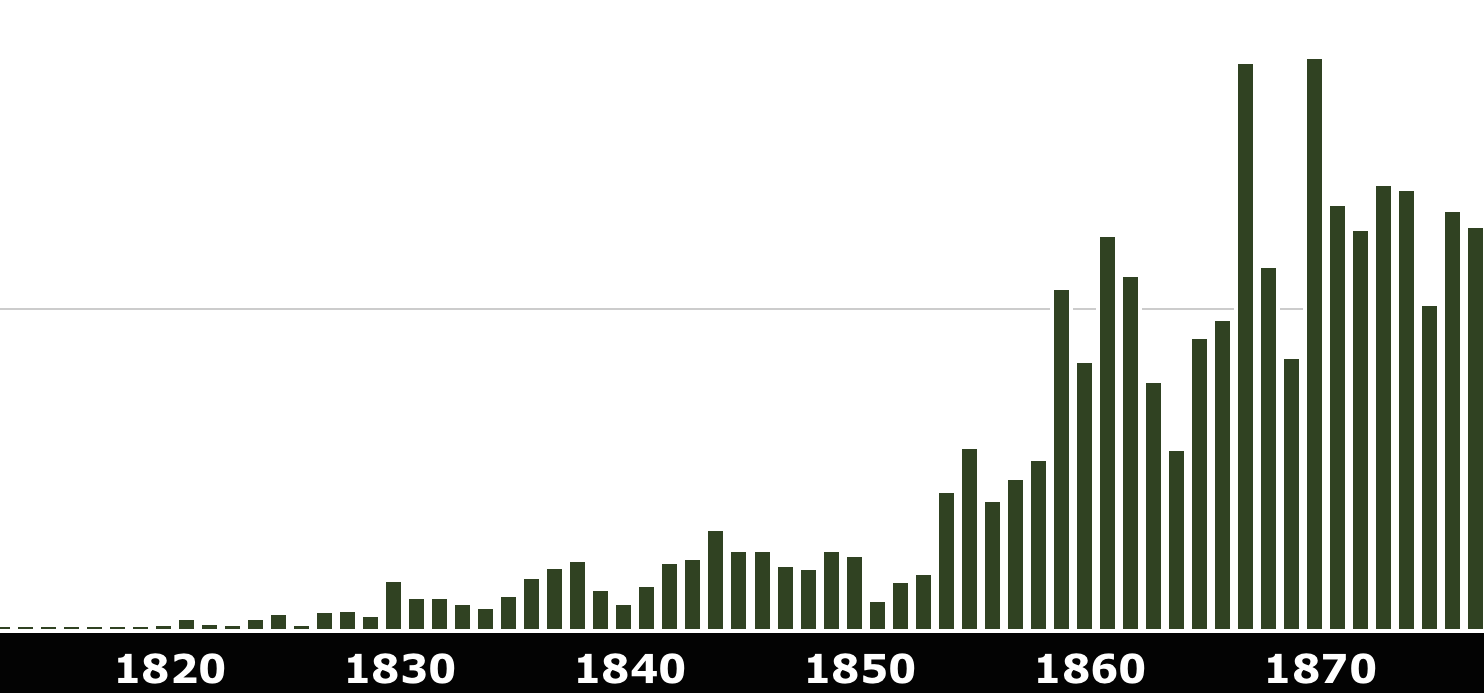

It was a particularly lucky chance that Darwin was conducting this experiment during the visit of the Harvard botanist Asa Gray and his wife Jane Gray wrote a letter to her sister describing the experience and the comic effect it had on the visitors who went off afterwards and practised making faces in front of their mirrors. Darwin began his experiment when he and his family were staying with relatives in London in March 1868 but continued it - recording the results on separate sheets of paper - when they returned home to Down House. The first set of visitors, whom Darwin described just as the "Hensleighs", we know from Emma's diary were their cousin Hensleigh Wedgwood and his two sons, Alfred Allen Wedgwood and Ernest Hensleigh Wedgwood who came to dinner on 22 March 1868. Darwin took advantage of being in London to get the opinion of a number of his naturalist friends - Edward Blyth, Henry Trimen,Thomas Henry Farrar , and George Henslow - and also of family friends Godfrey and Beatrice Lushington; his son Horace also joined in. Henslow, the last London visitor, called on Tuesday 31 March. Back at home in Kent, he continued the experiment immediately: the date of Sefton Strickland's visit is not recorded - he was a friend of Darwin's son, William - but another son, George came home on 4 April and the Huxleys visited on 18 April. The experiment concluded with the opinions of the sculptor Thomas Woolnerwho was working on a bust of Darwin - he called on Thursday 19 November.

Darwin's experiment

Darwin's aims

Darwin's experiment was part of this wider investigation; he wanted to test whether his own impression that the photographs were accurate portrayals was correct, or whether he had been influenced by reading the text that accompanied them. He was also particularly interested in any evidence suggesting that expressions could not be accurately simulated at will. He did not set out, as modern facial recognition experiments do, to assess his visitors' ability to identify emotional nuances. Darwin wanted to determine the accuracy of the photographic representations themselves, and the accuracy of Duchenne's galvanic stimulation method to artificially represent emotions.

Darwin's method

This is how Darwin described his method in Expression:

Darwin also claimed in a letter to James Crichton-Browne that he had not led his witnesses, but that the photographs had been tested by "showing them to many persons without any explanation and asking what they meant" [ Crichton-Browne, 22 May 1869]. Such an experiment would be described today as a "single-blind" test, but the tables suggest that Darwin was refining his method as he went: the first batch of visitors saw only seven of the eventual set of eleven photographs, and the first few responses consisted of "yes/no" answers, suggesting that, rather than asking what the expression was, Darwin had asked simply whether the photographs showed what they were supposed to. There are also signs that Darwin had erased and inked over some of the data in the first table. Back in Down, Darwin added three more photographs to his set (emotions 8, 9, and 10); the final photograph (11), was an afterthought, added in August when Susan Horner and the Pertz family visited. Most of the writing on the tables is Darwin's own, but in a few cases the answers are in other hands, possibly those of the visitors themselves. Darwin colour-coded the responses, marking those that agreed with the original description in blue crayon and those that didn't in red, deciding as he went which descriptions were close enough to the original to count. Darwin's experiment was not a scientific experiment as we understand it today: there was no control group, the experimental materials were not consistent across the whole trial, and he used a very small number of test subjects by modern standards, but this was pioneering work in a field where methodology is still debated.

Emotion 1

Darwin's results tables

Darwin compiled this first table of results between 22 and 31 March 1868 towards the end of a month-long visit to relatives in London. We don't know when he acquired his copy of Duchenne's book, but possibly during this visit. He and his family were staying with Emma Darwin's sister, Sarah Elizabeth Wedgwood at 4 Chester Place, near Regent's Park. Charles and Emma's cousin Hensleigh Wedgwood lived opposite. The range of visitors shows that the Darwins were far from antisocial and that Darwin took the opportunity of being in London to keep up his scientific contacts as well as his family ones. The "yes/no" responses of the first few columns quickly give way to more nuanced answers, suggesting that Darwin was refining his methodology as he went along.

| Hensleighs | Blyth | Trimen | Horace | Mrs Lushington | Mr. L. | Mr Farrar | Henslow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laughter | Yes, yes, yes | No | Yes | Yes | Amusement | Trying to laugh | Laugh | Yes |

| Astonishment | Yes, yes, yes | Yes | No | Yes | Disgust & wonder | Stupid wonder | Fearful astonishment | Surprise & horror |

| Fright | Yes, no, yes | Yes | Fright | Yes | Pain | Horror | Pain & disgust | Terror & horror |

| Despair & grief | Yes, no, yes | No | Disgust | No | Intense annoyance | Submission | ? | Incredulity, extreme |

| Torture, agony | Yes, no, yes | Yes | Pain | Yes | Fright | Great sudden pain | Startled expression | Torture |

| Crying | No, no, no | No | Doubt expression | Yes | Sadness | Bereavement | Sad | Looking an intense light |

| Laughing & crying | Laughing Yes | Both sides wrong | Yes 0 | Yes 0 | Yes 0 | Yes Yes |

Visitors

| 22 March 1868 | 24 March | 25 March | 28 March | 31 March | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hensleigh Wedgwood Alfred Allen Wedgwood Ernest Hensleigh Wedgwood | Edward Blyth | Henry Trimen | Horace Darwin | Beatrice Anne Lushington Godfrey Lushington Thomas Henry Farrer | George Henslow |

Back home at Down House in Kent, Darwin continued the experiment almost immediately, and in a more organised fashion, using a larger sheet of paper and drawing the table with a ruler, though he forgot to leave a row for the names of the visitors. He added three extra photographs immediately, all of negative emotions - suffering, deep grief, and fright - and then in August included one that was supposed to show hardness, and about which he felt particularly sceptical. His letters at the time show him juggling various research interests including a preoccupation with the muscles used in crying and screaming. See for example his letter to his son William, of 8 April [1868]: Darwin asked William to find London surgeons who could make observations for him. [ read letter ]

| Strickland | George | Huxley | R. Ruck | Clement Wedgwood | Miss S. Horner | Miss Pertz | Mrs Pertz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laughter (1) | Intense amusement | Laughter | Wicked joke | Bewilderment | Amusement | Half-laughing and half amazed | Pain | |

| Astonishment (2) | Woeful astonishment | Surprise | Surprise | Astonishment | Surprise | Terror | Surprise | Astonishment |

| Fright (3) | Horror | Terror | Extreme horror, Fright | Terror | Horror | Extreme discomfort | Fear | Dismay |

| Despair & Grief (4) | Contempt | Dejection | Contempt (Bearing pain Miss Th.) | Hatred | Supercilious contempt owning to lower lip | Disgust | Disgust | Misery |

| Torture & Agony (5) | Disgust | Rage | Torture, agony | Anger | Anger | Pain | Horror | Terror |

| Face Crying (6) | Crying | Commencement of extreme agony | Pain | Jocund | Ready to cry | Measuring a distance | Pain | |

| Laughing, Crying (7) | Tickled, amused | Laughter | Fun | Amusement | Laughing | Laughing | Assert with laughing | Laughing |

| 0 | Grief | 0 | Disgust | 0 | Arrogance | Arrogance | Suffering | |

| Suffering (8) | Enquiry thought | Surprise & incredulity | Pain | Puzzlement | Tragic feeling | Tragic feeling | Annoying | |

| Deep Grief (9) | Sorrow | Grief | Patient suffering | Grief | Grief | Tragic feeling | Sorrowful | Melancholy |

| Fright & Pain & Torture (10) | Fright | Terror | Surprise & Horror | Agony | Horror verging on madness | Extreme terror | Anger or Terror | Fright |

| Hardness (11) | Surly Reserve | Decided character | Thought |

Visitors

| 31 March | 18 April | 6 June | 28-29 August | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sefton West Strickland | George Howard Darwin | Thomas Henry Huxley 2486 | R. Ruck | Clement Francis Wedgwood | Anne Susan Horner either: Annie Pertz or: Dora Pertz Leonora Pertz (Mme Pertz) |

Entries became more intermittent after the end of April 1868. We don't know what Darwin's selection criteria were for his test subjects, or whether they were volunteers, or conscripts. There is a much higher proportion of women in the later stages and Darwin did refer to having shown the photographs to a wide range of different people so it is possible he was consciously picking and choosing from among his visitors; the empty column for Sophy Wedgwood suggests he wanted her to participate but that for some reason she didn't. The Darwins were away again in July, in the Isle of Wight, where they met both Tennyson and Longfellow, but sadly neither poet took part - perhaps Darwin had not taken the photographs away with him.

| Amy Crofton | Lucy Wedgwood | Sophia Wedgwood | Crotch | Dr Gray | Mrs Gray | Mrs Hooker | Mr Woolner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Laughter | Amusement | Pleasure | Laughing | Laughter | Laughter | Grinning smile | Laughter | |

| 2 Astonishment | Surprise | Surprise | Surprise Astonishment | Pain & wonder | Stupid wonder | [Sleepy smi]deleted | Wonder | |

| 3 Fright | Horror | Horror | Scared | Pain | Abject terror | Horror | Horror | |

| 4 Despair & Grief | Grief | Pain | Sudden grief | 0 | Pain or contempt | Contemptuous anger | Disgust | |

| 5 Torture & Agony | Calling out from sudden pain | Cry of anger | Sudden anger | Contemplating a catastrophe & fearing it would come on selfcurious fear | ||||

| 6 Crying | Sorrow | Distress | Cunning leer | 0 | Grief peevish | Endurance of pain | Mistery, just giving way | |

| 7 Laughing, crying | Laughter | Amusement | Smiling | Merriment | Do | 0 | Ironical laughter | |

| Anger | Trying to stop laughing | 0 | Satisfaction | Fun | Cunning | Like 6, intern misery | ||

| 8 Suffering | Trying to understand | Pain or distress | Subdued sorrow | 0 | Curiosity | Puzzle bewilderment | Bewilderment | |

| 9 Deep Grief | Grief | Thoughtful sorrow | To move compassion | Scorn | Despairing sorrow | Suffering endurance | An unhappy gentleman | |

| 10 Fright with agony | Seen a ghost | Horror | Extreme horror | Suffering | Agony | Terror | Horror | |

| 11 Hardness | Contempt or reproof | 0 | Cynical pride | 0 | 0 | Nothing |

Visitors

| 21 Sept | 8 Oct | 24 Oct | 19 November | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amy Crofton | Lucy Wedgwood Katherine Elizabeth Sophy Wedgwood | George Robert Crotch | Asa Gray Jane Loring Gray Frances Harriet Hooker | Thomas Woolner |

References

The tables of results are in the Darwin Archive of Cambridge University Library. In chronological order they are: DAR 186: 27, DAR 186: 29, DAR 186: 28. Darwin's copy of Duchenne is in the Darwin Library at Cambridge University Library, DAR LIB 160.