From Jean Jacques Moulinié 15 February 1869

Geneva

15th February 1869

Dear sir,

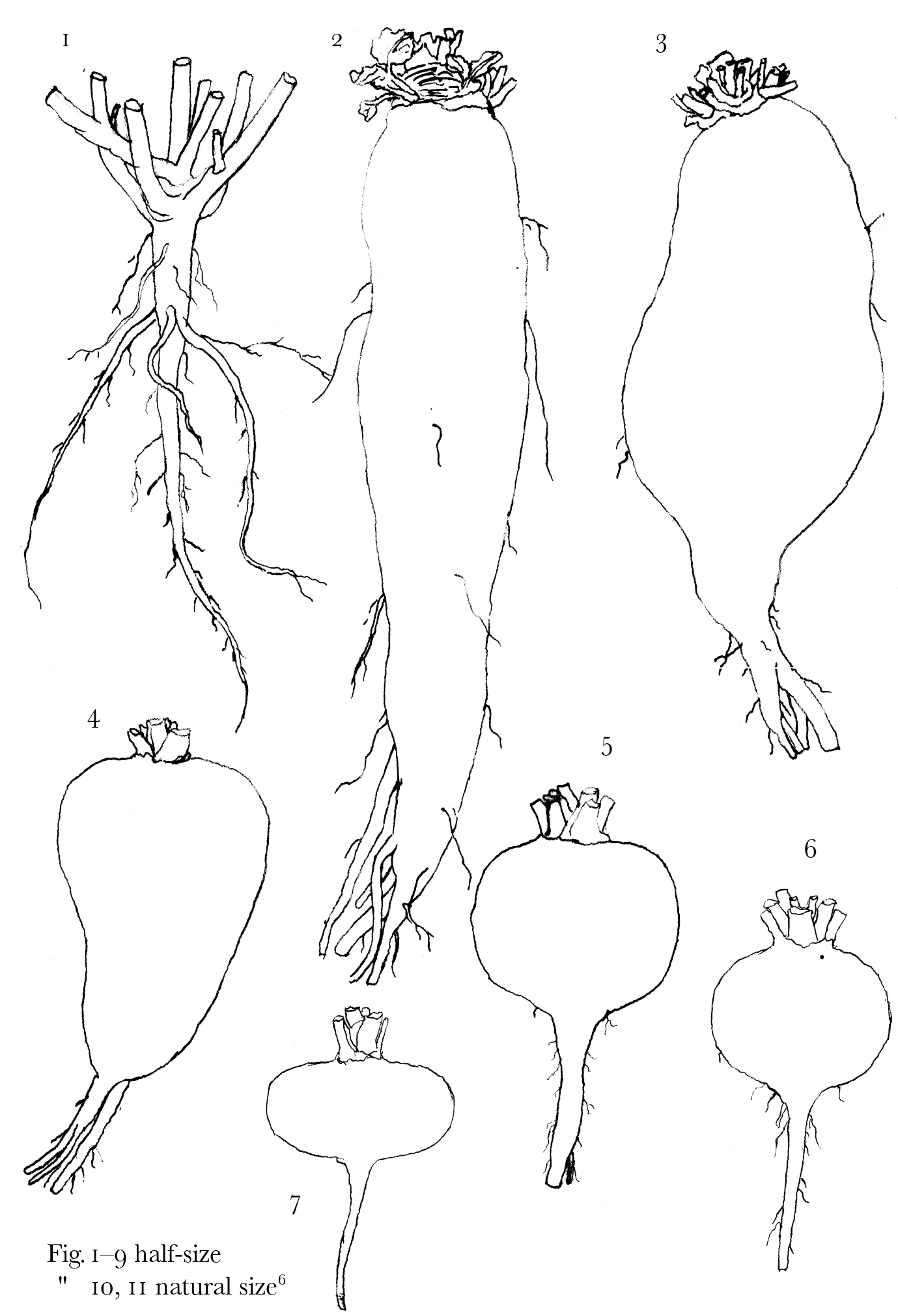

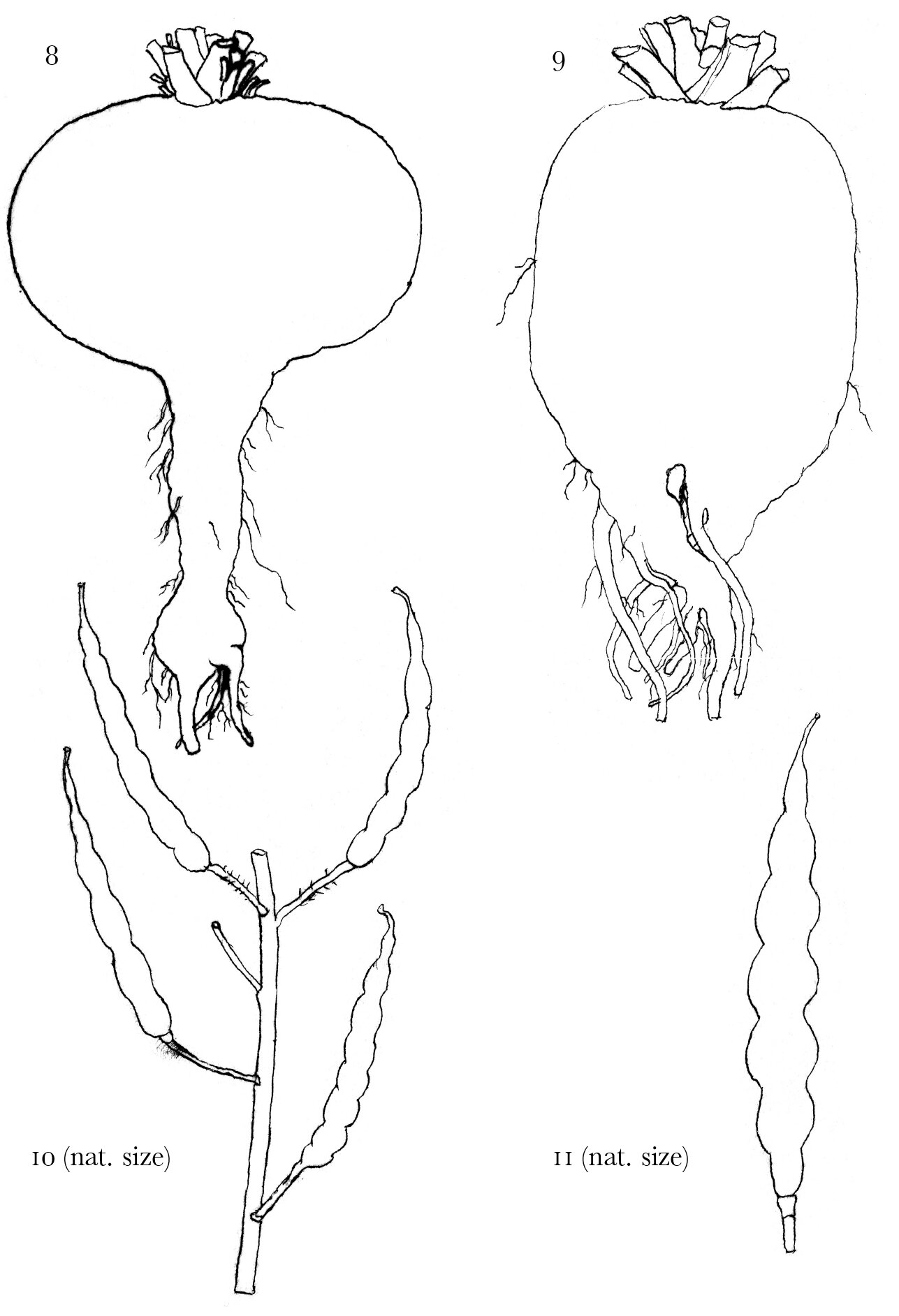

In perusing a french periodical intitled Journal d’Agriculture pratique, published weekly in Paris, I fall on an article published by a Mr. Carrière,1 concerning a very curious case of variation observed on the wild radish (Raphanus raphanistru⟨m)⟩; and describing the remarkable results obtained in a very short time, by selection and a rational cultivation of that wild plant. Thinking that the case, owing to the paper in which it is published, and which is perhaps not much known in England, might not come to your knowledge,—and may be of some interest for you,—I inclose hereby,—with a rough outline of the woodcuts accompanying the notice, and showing the wonderful differences obtained after four generations only, between the wild radish roots and those of the derived varieties improved by selection,—an abstract of the author’s paper, describing the experiment, its results, and the very simple process followed by him.2

Hoping that my little abstract, from your being still unacquainted with its object, may have some interest for you, and still more that this letter may find you in good health, pray, dear Sir, present my respectful compliments to Mrs. Darwin, remember me kindly to all the members of your amiable and hospitable family,3 and believe me | your’s ever and truly devoted | J. J. Moulinié

[Enclosure]

Journal d’Agriculture pratique. T. I, No. 5, 1869. 33e Année; p. 159. Paris.— Rédacteur en chef, E. Lecouteux.4

The wild radish improved, an insight on the origin of cultivated plants, in reference to Raphanus raphanistrum. | by Mr. E. A. Carrière.

The Raphanus raphanistrum is a wild plant well known by agricultors as a very inconvenient weed, for its tendancy to invade with much tenacity cultivated fields. It belongs to the Cruciferae, and has some likeness with the Sinapis arvense,5 with which it is often mistaken. Its flowers are sometimes of a pale yellow, sometimes white or streaked with lilac. Having remarked some analogy between the fruit of the garden radish and that of the wild R. raphanistrum, the author gathered some of this last’s seed, sowed it in good soil, during five years, each time selecting with care the seeds borne by the plants modified in the most advantageous manner. The experiment was pursued in two different conditions; in Paris, in the dry and light soil of the Museum’s nursery gardens; and in the country, in a heavier, calcareous and clayish ground. The results of the two trials were similar but not identical. In Paris the elongated napiform shape was predominant in the roots; in the country it was the reverse. In Paris the roots were all white or pink, while in those raised in the country, besides those two colours, a great many were very dark lilac or brown, some nearly black, and others of all shapes and colours representing all the various known forms of radishes & turnips, and much alike them, though not identical. One particular root (fig. 3) quite similar to the large China-radish, had a particular savour, between that of radish and turnip. Another (fig. 5) had a fine lilac skin, with flesh of the same colour and was consequently amongst vegetables, analogous to the red fleshed beetroot, the lilac potato; and certain flesh-coloured peeches & pears amongst fruit.

| Table of characters of R. raphanistrum wild, and of its cultivated varieties, compared. | |

| R. raphanistrum. | Varieties derived. |

| Flowers, pale yellow or white, sometimes slightly streaked with lilac. | Flowers, white, yellow or lilac-pink, sometimes of one colour, oftener streaked. |

| Pods, small, inclined, hard. | Pods, variable in size and shape, inclined, sometimes erect, sometimes as large and long as the pods of Madagascar radish, and then fleshy and good for eating. |

| Roots filiform, dry, fibrous, uniform, always white, hard, subligneous, uneatable. | Roots large, sometimes enormous, fleshy, varying considerably in shape and colour; flesh, white, sometimes pinkish or yellowish, sometimes lilac, juicy, soft, and eatable. |

| Figure 1, | represents half-size, the roots of the wild plant at full growth, weighing 22 grammes, white, hard, and quite uneatable. |

| Fig. 2. | root white, top lilac; total length 0.45 centimeter;—largest diameter 0.06 cent.:— weight 345 grammes. |

| Fig. 3. | Colour fine dark reddish pink, with top nearly lilac, hardly to be distinguished from the China-radish.— Total length, 0.40 cent.— diameter, 0.09 ct.— weight, 445 gr. |

| Fig. 4. | White, with a lilac hue at the summit.— Length 0.25 ct.— diameter, 0.07 ct.— weight 201 gr. |

| Fig. 5. | Dark black-lilac, veined; flesh lilac, with darker shades and streaks to a depth of 0.01 ct.;—the rest of the pulp being of a purplish white.— Length 22 ct. —diameter 0.07 ct.—weight 145 gr. |

| Fig. 6 | Dark black chesnut skin; flesh milky white, very soft. Length, 27 ct.,— diameter, 0.06ct.;— weight 87 gr. |

| Fig. 7 | Skin delicate and thin, of a fine pink colour; flesh of a very juicy and melting quality. This root spreads near the surface like certain breeds of turnips, and owing to its wide and flattened shape, much ressembles the fine radishes that gardeners select for seed. Length 0.12 ct.— Diameter, 0.06 ct.— Weight, 68 gr. |

| Fig. 8 | This root has a pinkish brick colour: skin wrinkled, as embroidered; flesh pink, with red streaks or veins to 0.01 centimeter’s depth, the rest being of a light flesh- coloured white. Length, 0.26 ct;— diameter 0.13 ct:— weight 625 gr. |

| Fig. 9. | White, smooth and glossy skin; ressembling much a good kind of turnip. Length, 0.32 ct.; diameter, 0.10 ct.— weight 651 gr. |

| Fig. 10 | Fruit branch of the wild radish, R. raphanistrum, —natural size. |

| Fig. 11. | Pod of the same, improved by cultivation. Natural size. |

All these roots though so different in shape and colour, were juicy, with a plain and marked flavour of radish, in some much like that of black radish. Tasted with care, a certain sweet flavour can be detected in several, reminding somewhat that of turnips, very slight in the raw state, but strong when cooked, the astringency of the radish disappearing completely. In the roots exposed to the air, and undergoing decomposition, the same smell of turnips was sensible. Their flesh was not quite similar to the radish, but more consistent, hardly sweet, and somewhat flowery, consequently more nutritious.

Here is a plant that can be ranked neither amongst radishes nor turnips, but partakes of the two, of radish when raw, of turnips when cooked, though generally the radish flavour is preponderant. This vegetable has been found excellent by all who have tasted it; the roots of all size are never hollow, and can be kept with all their qualities, for months in the cellar, and be used during the whole winter.

After some remarks on the effects of exterior conditions, and particularly the influence of the soil in modifying plants, shown by the different results obtained in the country soil, where the short roots were preponderant; while in the light and deep soil of Paris, they were exclusively long, white or slightly purplish (fig. 2), though all were derived from the same seed, the author concludes his paper in giving the best process to be used, and how selection must be practised in order to obtain in the quickest manner the desired modifications.

The object being the greatest growth of the underground part of the plant, he starts from seeds taken on the wild individuals which present already the largest roots, and continues in the same way with the offspring. The period of sowing the seed is not indifferent and must vary according to the part of the plant that is to be improved, so that it may come to its full growth.

To get large pods or improve any other aerial part, the seed must be sown in April or May, in a rich soil, in the best conditions of growth possible, and the best seed of the best plants selected for the next generations till the desired end be obtained.

To improve and increase the size of the roots, the seed must be sown in the beginning of September, so that the plants should not grow to seed the same year. When the cold season approaches, they are to be pulled out; and kept during the winter, sheltered from the frost, in a cool place, all their leaves, excepting those of the central part of the collar, being taken away. Next spring as soon as frost will be over, the finest of these wintered plants will be replanted in the best conditions, and their mature seed sown the same year, and the same process will have to be continued till the breed be fixed. Four generations and five years have been sufficient to give the results figured 2–9.

To improve rapidly and transform the R. raphanistrum, gather seed on the wild plant, sow it the next spring in a good soil, in favouring its growth by all possible manner. On the most vigourous plants choose again the finest seed, to be sown the same autumn, and continue in the same manner till the desired results be obtained.

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Carrière, Elie Abel. 1869. Origine des plantes domestiques démontrée par la culture du radis sauvage. Paris: the author.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Variation 2d ed.: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2d edition. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1875.

Summary

Sends abstract of an article by Carrière [J. Agric. Pratique 1 (1869): 159–67] on the improvement of wild radish by selection.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-6615

- From

- Jean Jacques Moulinié

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Geneva

- Source of text

- DAR 171: 272; DAR 193: 59–62

- Physical description

- ALS 2pp, encl 6pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 6615,” accessed on

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 17