From Fritz Müller 21 January 1879

Blumenau, St. Catharina, Brazil,

January 21, 1879

My Dear Sir,

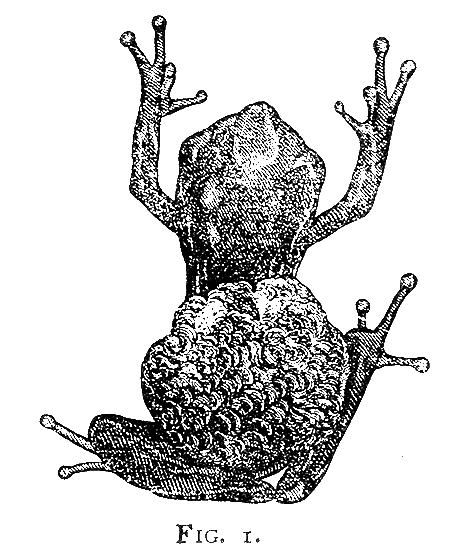

If I remember well, I have already told you of the curious fauna which is to be met with between the leaves of our Bromeliæ.1 Lately I found, in a large Bromelia, a little frog (Hylodes?), bearing its eggs on the back. The eggs were very large, so that nine of them covered the whole back from the shoulders to the hind end, as you will see on the photograph accompanying this letter, Fig. I (the little animal was so restless that only after many fruitless trials a tolerable photograph could be obtained). The tadpoles, on emerging from the eggs, were already provided with hind-legs; and one of them lived with me about a fortnight, when the fore-legs also had made their appearance. During this time I saw no external branchiæ, nor did I find any opening which might lead to internal branchiæ.2

There is here another locality in which a peculiar fauna lives, viz., the rocks of waterfalls, which are of very frequent occurrence in almost all our mountain rivulets. On these rocks, along which the water is slowly trickling down, or which are continually wetted by the spray of the waterfall, there live various beetles not to be met with anywhere else, larvæ of diptera and caddis-flies, and a tadpole remarkable for its unusually long tail.

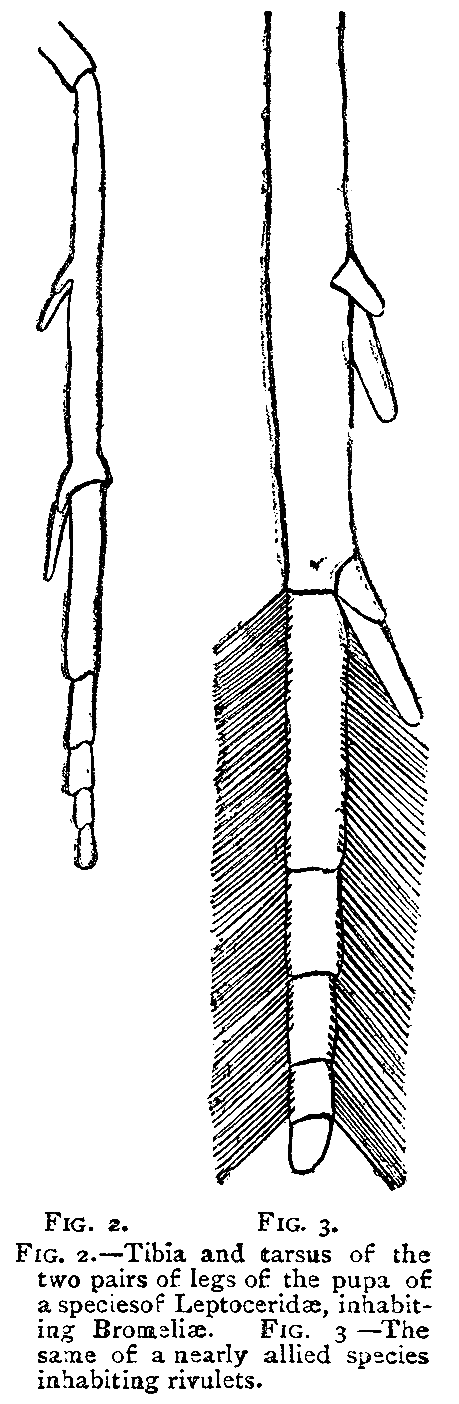

The pupæ of caddis-flies living on the rocks of waterfalls (I examined three species belonging to the Hydropsychidæ, Hydroptilidæ, and Sericostomatidæ (Helicopsyche)), as well as those living in the Bromeliæ (a species belonging to the Leptoceridæ), are distinguished by a very interesting feature.3 In other caddis-flies the feet of the second pair of legs (and in some species those of the first pair also) are fringed in the pupæ with long hairs, which serve the pupa, after leaving its case, to swim to the surface of the water for its final transformation. Now neither on the surface of bare or moss-covered rocks, nor in the narrow space between the leaves of Bromeliæ, the pupæ have any necessity, nor would even be able, to swim, and in the four species living on such localities which I examined, and which belong to as many different families, the feet of the pupæ are quite hairless, or nearly so, while in allied species of the same families or even genera (Helicopsyche) the fringes of the legs, used for swimming, are well developed.

This abortion of the useless fringes in the caddis-flies inhabiting the Bromeliæ and waterfalls appears to me to be of considerable interest, because it cannot be considered, as in many other cases, as a direct consequence of disuse; for at the time when the pupæ leave their cases and when the fringes of their feet are proving either useful or useless, these fringes as well as the whole skin of the pupa, ready to be shed, have no connection whatever with the body of the insect; it is therefore impossible that the circumstance of the fringes being used or not for swimming, should have any influence on their being developed or not developed in the descendants of these insects. As far as I can see, the fringes, though useless, would do no harm to the species, in which they have disappeared, and the material saved by their not being developed appears to be quite insignificant, so that natural selection can hardly have come into play in this case. The fringes might disappear casually in some individuals; but, without selection, this casual variation would have no chance to prevail. There must be some constant cause leading to this rapid abortion of the fringes on the feet of the pupæ in all those species in which they have become useless, and I think this may be atavism. For caddis-flies, no doubt, are descended from ancestors which did not live in the water, and the pupæ of which had no fringes on their feet. Thus there may even now exist in all caddis-flies an ancestral tendency to the production of hairless feet in the pupæ, which tendency in the common species is victoriously counteracted by natural selection, for any pupa, unable to swim, would be mercilessly drowned. But as soon as swimming is not required and the fringes consequently become useless, this ancestral tendency, not counterbalanced by natural selection, will prevail, and lead to the abortion of the fringes.

I do not remember having seen, in any list of cleistogamic plants, the Podostemaceæ. These curious little aquatic plants, which Lindley placed near the Piperaceæ, Kunth between the Juncagineæ and Alismaceæ, and which Sachs considers as being of quite dubious affinity, cover densely the stones in the rapids of our rivers;4 on the branches which come above the surface of the water, there are pedunculated, open, fertile flowers; but there are numerous sessile flower-buds also on the branches, which probably remain submerged for ever; I have not yet ascertained whether these submerged flowers are fertile; if they are so, they can hardly fail to be cleistogamic.

Fritz Müller

Footnotes

Bibliography

Duellman, William E. and Trueb, Linda. 2015. Marsupial frogs: Gastrotheca and allied genera. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kunth, Karl Sigismund. 1831. Handbuch der Botanik. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot.

Lindley, John. 1846b. The vegetable kingdom. London: the author.

McLachlan, Robert. 1873. A catalogue of the neuropterous insects of New Zealand; with notes, and descriptions of new forms. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 4th ser. 12: 30–42

Summary

Has lately found frog that has eggs on its back.

Pupae of caddis-flies living on rocks have lost fringe of hairs on their feet. In species that live in the water these are used for swimming.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-11839

- From

- Johann Friedrich Theodor (Fritz) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Santa Catharina, Brazil

- Source of text

- Nature, 20 March 1879, pp. 463–4

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 11839,” accessed on