To Gardeners’ Chronicle [before 5 January 1861]1

[Down]

Mr. James Drummond sent me a packet of seeds of this plant from Swan River,2 with the following memorandum:—“The achenia of several small composite plants, more especially of that above named, are blown about by the wind till a shower of rain falls, when they attach themselves by a gummy matter to the soil by their lower ends, at the same time setting themselves perfectly upright. They ornament many a barren spot in this country throughout the dry season, and they are not easily removed even when the ground is flooded by thunder storms.”

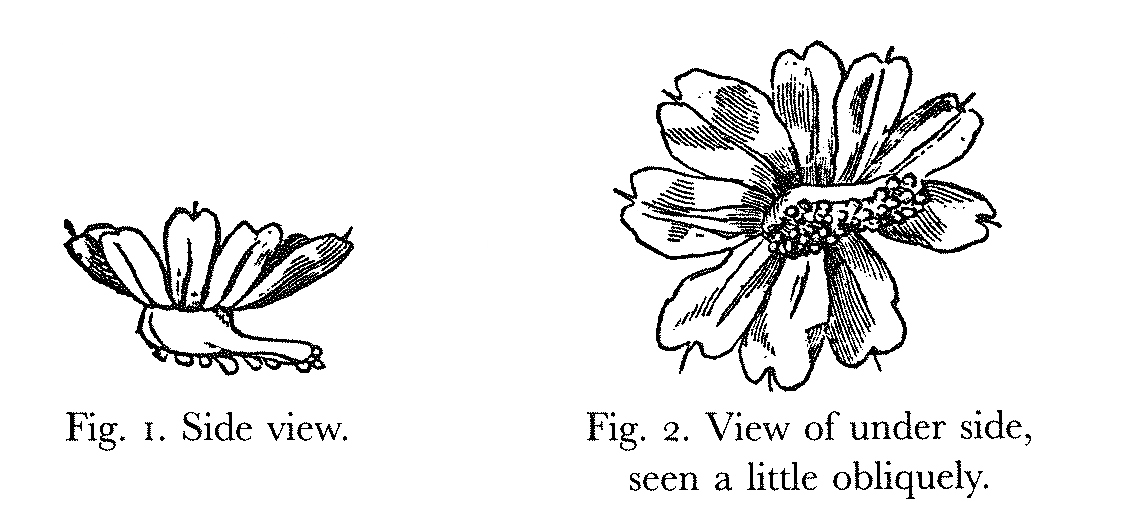

The achenia of the Pumilio are singularly-shaped bodies; the calyx (pappus) consists generally of nine scales or sepals, expanded like a flower, with each sepal beautifully ornamented by branching lines; the lower part, including the seed, is bent towards one side (see Fig. 1) at nearly right angles, and somewhat resembles a human foot in shape. The upper side or instep of this foot is smooth, but the toe and the sole, which is about 1-25th of an inch in length, is covered (see Fig. 2) with from 30 to 40 imbricated little bladders. Each bladder is oval and 1-200th of an inch in length, and is formed of thin structureless membrane, enclosing a hard ball of dry mucus or matter which becomes adhesive when moistened. The sole or the achenium is pitted where the bladders are attached3 but these do not open into its interior. When the achenia are placed in water or on a damp surface, the bladders in a few minutes all burst longitudinally and discharge their contents, rendering a large drop of water very viscid. This viscid drop does not diffuse itself throughout the water, like gum, but remains surrounding the achenium. When dried it becomes stringy, and will again rapidly absorb moisture and swell. Spirits of wine does not cause the bladders to burst, and it renders the mucus slightly opaque.

If a pinch of these achenia be dropped from a little height on damp paper, the greater number fall like shuttlecocks, upright and rest on the sole; the bladders then quickly burst, and as the paper dries the seeds become firmly attached to it. Many achenia, however, drop so as to rest on one edge of the sole, and in this case the drying of the mucus pulls the upper edge of the sole down, and so places the flower-like calyx nearly upright. Any one looking at a piece of paper over which when damp a number of achenia had been scattered by chance would conclude that each one had been placed upright and carefully gummed.

If an achenium falls upside down, so as to rest on the tips of the calyx, the sole does not touch the damp surface, yet moisture is so rapidly absorbed by the sepals, that in seven minutes I have seen the bladders burst: in this case as the paper dries the exuded mucus dries on the surface of the sole and the seed is not fixed; but if subsequently it be blown the right way up on a damp surface, the mucus will soften and act and attach it firmly. In so dry a climate as Australia the existence of these little bladders of dried mucus, having a strong affinity for water and becoming highly viscid on that side alone of the achenium which alights on the ground, seems a pretty adaptation to ensure the attachment of the seed to the first damp spot on which it may be blown. Whether the tendency of the achenia to place themselves upright be of any service to the plant would be hard to determine; but it seems possible that the salver-shaped calyx, which, as we have seen, so rapidly absorbs moisture and carries it down to the lower surface of the achenia, might aid in utilising dew or showers of fine rain.4

Charles Darwin

Footnotes

Bibliography

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Summary

Describes how adhesive bladders enable the achenia of Pumilio argyrolepsis to attach themselves to the soil. James Drummond sent seeds to CD with a memorandum on the achenia.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-3042

- From

- Charles Robert Darwin

- To

- Gardeners’ Chronicle

- Sent from

- Down

- Source of text

- Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette, 5 January 1861, pp. 4–5

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 3042,” accessed on 20 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-3042.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 9