From Adolf Ernst 7 August 1880

Caracas

August 7th 1880

Dear Sir,

Allow me to thank you most sincerely for your “Geological Observations”, which I have studied with great interest.1

In “Nature” you will have noticed an article of mine on the fecundation of Cobaea penduliflora, which I hope is not void of interest.2 I have to add two observations. In none of the many fruits of my plant, both the ovules were developed in all ovary-cells; whilst on plants growing in the forest I found many with fully developed six seeds. Should the former be a consequence of geitogamy?3 I know of no plant of Cobaea cultivated in Carácas; the nearest specimens are those of a country-garden, called El Paraiso, which is about 1600 meters from my house, as the crow flies; so that a cross-fecundation between specimens at both places appears next to impossible.— A very luxuriant specimen of Cobaea which I found lately in the forest, had almost overgrown a species of Byrsonima, so that the conspicuous yellow inflorescences of the tree appeared to belong to the climber, which was in flower too. May be the moths are attracted by the bright flowers of the Byrsonima, so that the tree would be a little more than the mere hold of the climber.4

I inclose some seeds of the Cobaea, as I think you might possibly feel interest in growing the plant.

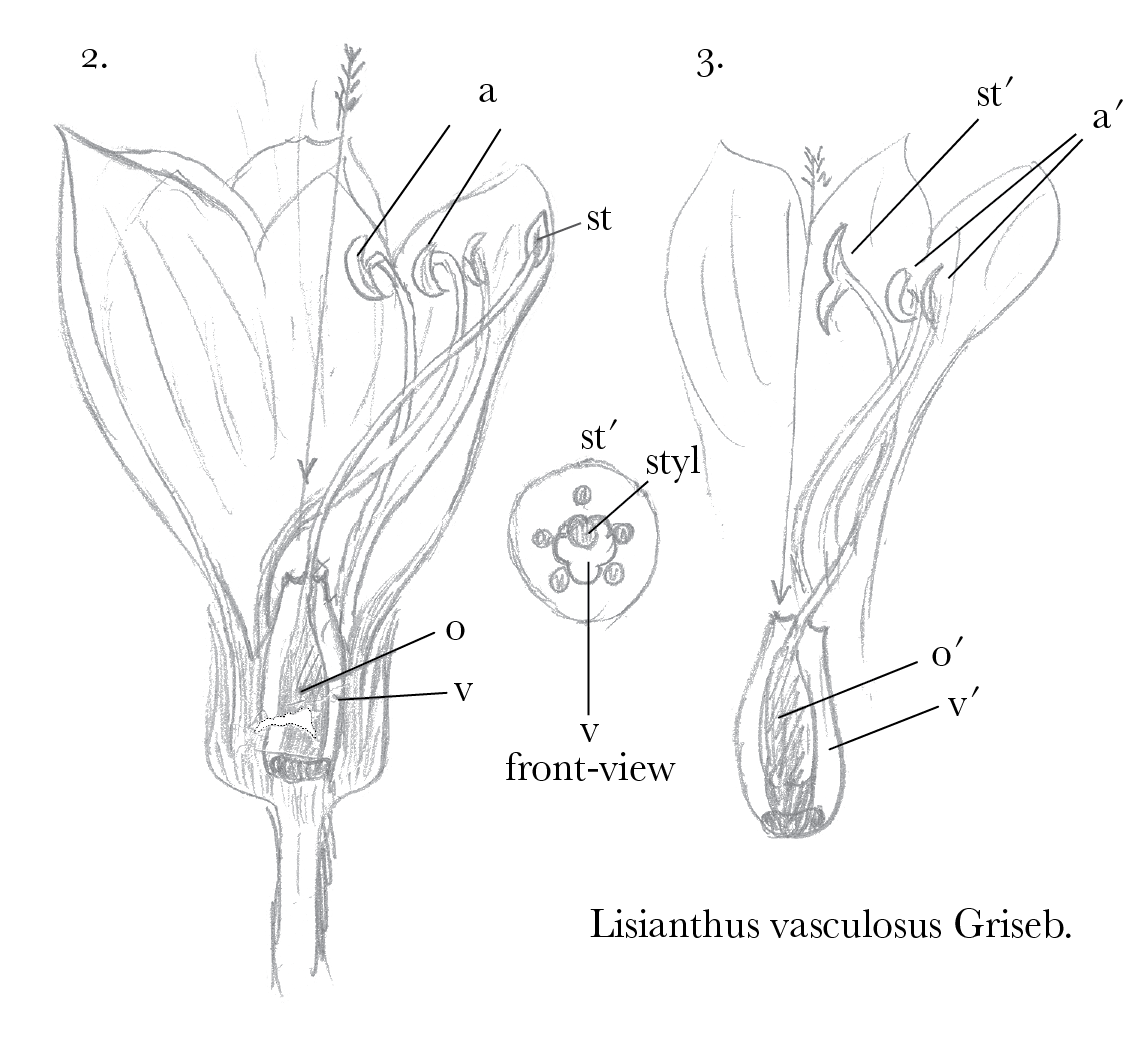

I inclose likewise a poor sketch of the flower of one of our few Gentianeae: Lisianthus vasculosus Griseb.—5 This half shrub grows in our higher mountains, from 5000 feet upwards. The drawing is natural size, but as I am unfortunately a very bad drawer, or none at all, I fear the sketch will scarcely give a good idea of the flower and its interesting structure.

The flowers grow in short cymes at the end of the branches, are rather fleshy, and have short and strong peduncles. They have generally a nearly upright position. The most peculiar part in their interior is a large vessel inclosing the ovary, and I think Grisebach gave the plant on this account the specific name vasculosus, though he does not even mention this structure in his description Linnaea XXII, 37, 38.6 This vessel is formed by the inferior part of the corollatube, whilst the brim is formed by a supra-staminal annular appendix of the same. It is about 15–16 millim. deep, at the mouth it is 5–6mm. wide, but at the bottom it is a little wider. The ovary is just in the middle of it, leaving a clear space of 2mm. on every side. This vessel is full of nectar. It is always open, the mouth shows no hairs, nor is there any other contrivance by which the nectar might be protected against unbidden guests. There is no fear of a natural outflow, as the flowers never have a nodding position.

The large funnel-shaped corolla is of a straw-yellow colour, with some very faint red stripes in the interior. The style rises in a somewhat curved line, and the unripe stigma touches closely the upper corolla-lobes, which are a little smaller than the lower ones. The former are at the same time reflexed at their apices, whilst the under ones remain straight, affording, as it were, a most commodious landing to any insect.

The stamens rise from the annular ditch between the corolla and the brim of the nectary, are curved, and bear also curved anthers, the convex side of which (where dehiscence takes place) turns towards the lower corolla lobes; but, as you will see from the sketch, a great part of the mouth is left free.

The flowers are most decidedly proterandrous, for the anthers burst long before the stigma opens; but flowers of all degrees of development are to be met with at the same time. An insect entering the corolla in the direction of the arrow will get at the nectar, but will also brush off a quantity of pollen and carry it away on its back.7

As soon as the anthers have done their work, the stamina withdraw close to the superior lobes, whilst the style with the opened stigma comes a little down, so that the latter lays now in the place where formerly the anthers were, as I try to show in figure 3. It is evident that an insect visiting a flower in this state, must leave some pollen on the stigma, which it cannot avoid to touch with its back.

About a fortnight ago I had the opportunity to witness the visit of these flowers by a large moth (Chaerocampa trilineata Walk), and I saw very distinctly that everything went on in the manner described. I secured the animal, and found its back indeed almost covered with pollen, which under the microscope proved to be that of Lisianthus. I likewise convinced myself that two of the flowers visited by the moth, had really more or less pollen on their stigmas, these two being the only ones which were in condition to be fecundated.—

The whole process has certainly nothing particular; but it appeared to me worth while to describe it at some length, as it is so extremely simple. Is there anything like in other species of Lisianthus? Mùller says nothing in his “Befruchtung der Blumen”,8 nor do I find anything referring to it in other books which I am able to consult. Some time ago I sent seed of Lisianthus vasculosus to Kew;9 I hope they will grow; the plant is rather showy and deserves a good plate.

I forgot to say that the flowers have no smell, however they are very conspicuous on account of their yellowish-white colour, which contrasts with the dark green foliage. The nectar is very sweet. It exists already in the flowers at the time of their opening, but not before, nor did I find any in flowers which exhibited some signs of having done their task; so that it certainly only serves indirectly the plant. I think thousands of cases of this character may be found against Bonnier’s views.—10

A friend of mine has in his garden a Physianthus (Arauja), which I believe to be the species albens, though there is no red at all on the pure white corolla.11 I recommended careful observations with respect to insects caught by this plant, reading to him the article in a late number of the American Naturalist.— Yesterday he brought me one flower, in which a honey-bee had been caught exactly in the manner as it has been described several times. The observations are continued with much care, as I should like to see whether there be any thing like the reported carnivorous habit of bees.12

I hope you will pardon my keeping up so much of your time with my long letters, especially as my observations may be of however small interest to you.

Allow me to continue my communications from time to time, and believe me one of your sincerest admirers and enthusiastic followers. | A Ernst

[Enclosure]13

Footnotes

Bibliography

Ernst, Adolf. 1880. On the fertilisation of Cobæa Penduliflora (Hook. Fil.) Nature, 17 June 1880, pp. 148–9.

Geological observations 2d ed.: Geological observations on the volcanic islands and parts of South America visited during the voyage of H.M.S. ‘Beagle’. By Charles Darwin. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1876.

Grisebach, August Heinrich Rudolf. 1849b. Gentianeae Juss. Linnaea. Ein Journal für die Botanik in ihrem ganzen Umfange 22: 32–46.

Kerner, Anton. 1876. Die Schutzmittel der Blüthen gegen unberufene Gäste. In Festschrift der K. K. Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. Vienna: K. K. Zoologisch-Botanische Gesellschaft; Braumüller.

Müller, Hermann. 1873. Die Befruchtung der Blumen durch Insekten und die gegenseitigen Anpassungen beider. Ein Beitrag zur Erkenntniss des ursächlichen Zusammenhanges in der organischen Natur. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Summary

Cobaea fertilisation.

Describes moth-pollination of gentian growing on Venezuelan mountains.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-12682

- From

- Adolf Ernst

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Caracas

- Source of text

- DAR 163: 22

- Physical description

- ALS 4pp, sketches 2pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 12682,” accessed on 16 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-12682.xml