From J. S. Henslow 19 April 1841

Hitcham Bildeston Suffolk

19 April 1841

My dear Darwin,

It is almost as strange for me to be writing to you from a sickbed, as if I were dating my letter from the top of Vesuvius— Don’t suppose however that I am very seriously ill—indeed I am so far well that Mrs Henslow has just set off for Bottisham,1 & I have just finished a hearty breakfast—but as I am under orders & must not get up for 2 or 3 hours, I cannot do better than write to you who have so often been in my thoughts during the last week— I suppose I must believe that I have had something of the Influenza—but if I were to trust my own judgment I should say I caught a violent cold at church yesterday week (Easter Sunday) which turned to sore-throat on Monday, & this being imprudently trifled with by my pottering about a damp outhouse arranging fossil plants &c—was determined to show me that it was the better man of the two, & so by Tuesday morning I found that I could not swallow & hardly speak— A blister-pilling—and saline-draughting—has so far set me to rights that I got down stairs yesterday—& to day feel as well as a man can after such sort of discipline— But I am told I must take some quinine for a few days— We are very fortunate here in a straightforward intelligent medical adviser—& I dare say he has treated me right—indeed my very foul tongue has satisfied me that I have had something beyond a usual attack of cold— He tells me that the use of the Tonsal glands is not known, & from people having had their Uvulus snipped off (as we lately read) for stammering—one would suppose such appendages were about as necessary as the crests on Lizards— But my experience of the use of a Tonsal last week suggests the idea that these supernumerary appendages are really important indigators of incipient disease— If my Uvula did not warn me in ordinary cases not to eat when I was about to have a cold—& it invariably does so—I should run a risk of neglecting the good old adage (so often misunderstood) of “Stuff a cold—&—starve a fever”—(the latter contingency viz. being hinted at as the consequent of the former)— So if my left tonsal had not absolutely hindered my eating much, almost any thing, at a dinner party on Monday, I should probably have aggravated the disease about me, of which I was otherwise all but unconscious—& instead of a week’s attack, I might have had one of much longer duration— At all events the inflamation & subsequent ulceration of the aforesaid Tonsal may have saved a like attack upon my pharynx or some other part of somewhat more importance to the animal economy— But I don’t know why I am writing all this stuff to you except that it has been running in my head, & you happen to be the first person who gets the outpourings at my pen—

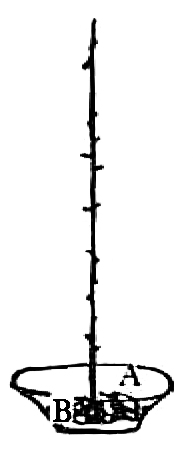

I had intended, when I began, to give you an account of a little pet of mine, which has amused the household, & seems to please every one who sees it—& is quite in your way— I mean a little harvest mouse I have had now for 3 or 4 months. The interest which it creates arises from the manner in which I keep it— I have a large washing basin (valuable to me as having belonged to poor Ramsay)2 & in the middle of this I have erected a spray of laburnum about 6 or 7 feet high—having cut off the lateral twigs to within about an inch. It is steadied in its position by a lump of lead at the bottom which I melted round it— I have a turf of grass & some moss in the bottom of the basin— At A. a pan containing some cotton wool— At B. a little pot for water— The basin being open at top— the mouse has all the appearance of being at perfect liberty—

only—he can’t get out— He is the most active little fellow imaginable— Runs up & down the stick perpetually— In ascending his mast he sticks is tail out quite straight—but in descending, he most curiously uses it as a prehensile tailed monkey does his—twisting it round the branch— When he comes to a projecting twig, the tail is loosened for an instant & then clasped tightly again—3 The bark at first was smooth & polished, & the lower part almost too much for him, being as thick as my finger, & it was very amusing to see his efforts at swarming up it—but now that it has got dry, he runs from bottom to top as readily as if he were on level ground— My basin is hardly deep enough, as he jumps very high, & at first I had not taken sufficient precautions to cut back the lateral twigs & the little fellow got away 4 or 5 times—but I always enticed him back by leaving the basin on the floor all night & putting two or 3 inclined twig’s from the edge to the ground, when he climbed up them & returned to his quarters— I give him wheat—but he always prefers nuts— He has had a companion for some weeks in a fat Dormouse—which remains snug in the cotton all day—but comes out in the evening & promenades up & down the stick— He has not the activity of the Harvest Mouse never uses his tail prehensilely—& often ascends by a sort of successive jerks—more à la Squirrel fashion—as he ought to do. I never saw him make any attempt to escape by jumping—but suspect he may at present be too torpid or too fat— He possesses one curious instinct—which reminds me of what you say of the Guanaco4 —for I find every morning that he has made use of the pan of water as a water-closet— Place it were I will, he always selects this as a convenient spot for the deposition of a considerable number of his coprolitic coagulations—& Master Mousey seems partially inclined to imitate so laudable an example— I had a great mind to draw up an account of Mouse-Keeping on the above principles for the use of those young ladies who delight in pet Dormi⟨ce⟩ & send it to the Annals of Natural History—but I shall not take the trouble to re-write the story— If however you happen to know any one whom you think the account would interest, & would let them see this, He, she, or they may work it out— An earthen footpan would answer as well as a bason—but a real amateur would send to the potteries for a mouse-Menagerie capable of holding a large apartment, & might add the shrews to them—

only—he can’t get out— He is the most active little fellow imaginable— Runs up & down the stick perpetually— In ascending his mast he sticks is tail out quite straight—but in descending, he most curiously uses it as a prehensile tailed monkey does his—twisting it round the branch— When he comes to a projecting twig, the tail is loosened for an instant & then clasped tightly again—3 The bark at first was smooth & polished, & the lower part almost too much for him, being as thick as my finger, & it was very amusing to see his efforts at swarming up it—but now that it has got dry, he runs from bottom to top as readily as if he were on level ground— My basin is hardly deep enough, as he jumps very high, & at first I had not taken sufficient precautions to cut back the lateral twigs & the little fellow got away 4 or 5 times—but I always enticed him back by leaving the basin on the floor all night & putting two or 3 inclined twig’s from the edge to the ground, when he climbed up them & returned to his quarters— I give him wheat—but he always prefers nuts— He has had a companion for some weeks in a fat Dormouse—which remains snug in the cotton all day—but comes out in the evening & promenades up & down the stick— He has not the activity of the Harvest Mouse never uses his tail prehensilely—& often ascends by a sort of successive jerks—more à la Squirrel fashion—as he ought to do. I never saw him make any attempt to escape by jumping—but suspect he may at present be too torpid or too fat— He possesses one curious instinct—which reminds me of what you say of the Guanaco4 —for I find every morning that he has made use of the pan of water as a water-closet— Place it were I will, he always selects this as a convenient spot for the deposition of a considerable number of his coprolitic coagulations—& Master Mousey seems partially inclined to imitate so laudable an example— I had a great mind to draw up an account of Mouse-Keeping on the above principles for the use of those young ladies who delight in pet Dormi⟨ce⟩ & send it to the Annals of Natural History—but I shall not take the trouble to re-write the story— If however you happen to know any one whom you think the account would interest, & would let them see this, He, she, or they may work it out— An earthen footpan would answer as well as a bason—but a real amateur would send to the potteries for a mouse-Menagerie capable of holding a large apartment, & might add the shrews to them—

A letter from Lyell a few days ago tells me you are much the same— I wish you were as well recovered as myself from my little memento— I go to Cambridge next Monday—

With kindest regards to Mrs D. believe me | ever | Yrs affectly | J S Henslow

CD annotations

Footnotes

Summary

Reports observations on the behaviour of captive harvest mouse and dormouse. When descending sticks mouse uses its tail like a prehensile-tailed monkey.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-598

- From

- John Stevens Henslow

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Hitcham

- Source of text

- DAR 166: 176

- Physical description

- ALS 8pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 598,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-598.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 2