From Hermann Müller 23 March 1867

Lippstadt,

march 23th 1867.

My dear Sir,

You have so kindly accepted of my inconsiderable first attempts at spreading your theories of infinite consequence among bryologists, that I feel compelled not only to thank you sincerely for your encouraging reply, but also to ask your advice with respect to my further activity in the above mentioned direction.1

After being employed, while adhering for many years to the premises of the Linnean School, in researches about insects, phenogams and mosses I was for the first time induced by your masterly work on the origin of species to a serious examination and thereby gradually to a torough rejection of my Linnean point of view.2 Innumerable phenomena of animal and vegetable life which I had by the bye observed as a diligent collector without being able to get to an understanding of or even to an universal interest in them appeared to me as it were magically illumined in their causal connection under the light of your theorie so that nothing in my life had made upon me a deeper impression nor given me a more lasting satisfaction than the study of your masterwork.

Although I am fully aware of the slight importance of the small memoirs which I have published till now uper mosses for the whole theory of species, I nevertheless did not keep them back, as you said yourself: “Whoever is led to believe that species are mutable will do good service by conscientiously expressing his conviction; for only thus can the load of prejudice by which this subject is overwhelmed be removed”.3

In future my endeavours will be directed towards contributing for my part to determine clearly by a close examination of several mosses the various gradations occuring between species and varieties as well as to state the gradations of advantageous properties in mosses—particularly of their hygroscopic organs—and to gain an understanding of their origin trough natural selection.

For next summer, however, I think I could not easily find a higher enjoyment and at the same time a better preparation for the researches intended than in repeating your charming observations on the fertilisation of Orchids by insects, as far as the Westfalian Flora offers any opportunities to it and in devoting my attention in general to the fertilisation of flowers by insects. As I have made for many years a thorough study of the indigenous plants and insects I do not think the task to difficult for me. Besides Sprengel “das entdeckte Geheimniss der Natur”, your own work on Orchids and several epistolary communications of my brother’s (Fritz Müller in Desterro) nothing on this subject has come to my notice.4 If, therefore, any other observations should have been published in that line of late, I take the liberty of asking you to let me kindly know them.

A lovely plant, equally subject to fertilisation by insects is at present blowing in its pot before my window. As I think it possible that nothing has been published yet on that mechanism, I venture upon adding herewith for you both figure and description5

Hoping that you will accept of these lines with the same benevolence as you did with respect to my small publications on mosses, I remain, | dear Sir, | Yours most respectfully | H. Müller.

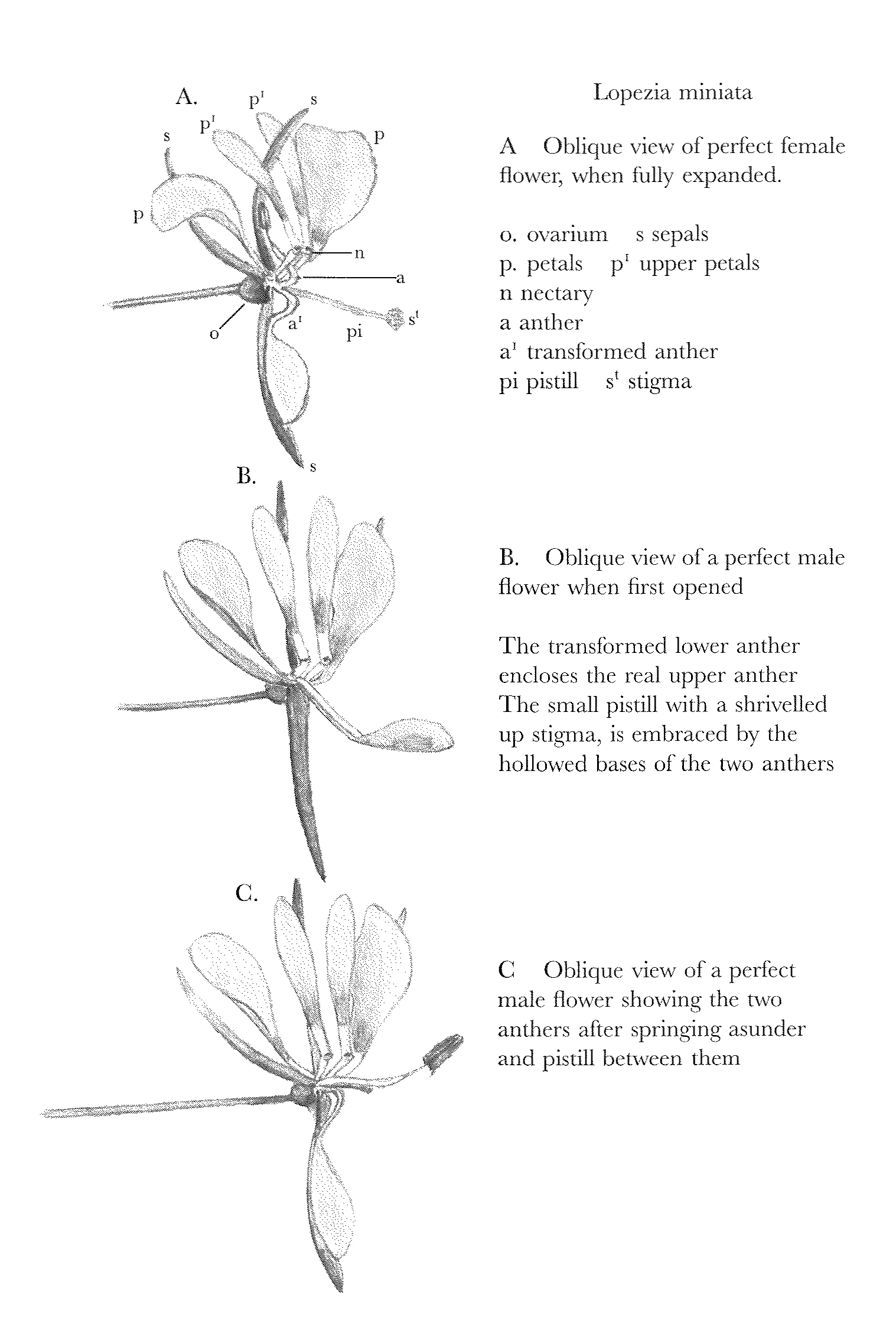

Description of the mechanism of the flowers in Lopezia miniata

The numerous little flowers distinguished by their vivid red colour are fixed upon long horizontally projecting pedicels in consequence of which their sepals and petals come to lie almost in a vertical plane and offer no landing place to an insect. The flowers consist of a globular ovarium 4 narrow sepals, 4 broader petals alternating with them, 2 stamina the one of which is so transformed that instead of the anthers it bears a petal like lamina which is in the middle line folded up upwards and a pistil.

Of the sepals two are lying in a vertical line, both the others are not rectangular to these, but form with the one above an angle of about 60 degrees. Of the petals the two superior narrower ones have their stalk shaped basis in a somewhat oblique direction upwards and are then suddenly bending in a right angle like a knee, so that their lamina stands vertical or bent a little backwards. Just on the knee which is mostly projecting in front there appears a small green shining spot secreting such a copious quantity of a liquid clear as whater and sweet as sugar that not only the knee itself is covered with a drop of nectar but also on the basis of the both inferior petals a still mor abundant quantity of the nectar is gathered. The inferior petals which ought to stand in the middle of the angle between the inferior and the lateral sepals are so strongly bent upwards at their basis, that their lamina attains a still higher position than the lateral petals At the same time the inferior margin of these petals bends so much upwards that by this double incurvation their basis is fitted for collecting the overflowing drops of the nectary.

Thus much all flowers are identic, yet with regard to the structure of the anthers and the pistill they are to be distinguished in two kinds which, it seems, appear irregularly mingled.6 With the one kind of mostly female flowers the straightly projecting pistil forms the landing place for the insects when they come flying. The real anther which seems to contain only shrivelled up grains of pollen, lies bent back as far as to be pressed against the upper sepal, likewise the transformed anther lies bent back and is pressed against the lower sepal

With the other mostly male flowers the anthers of the upper stamens which contains a copious quantity of good pollengrains are firstly closed round by the clasped or folded up lamina of the transformed anther and open in that confinement by two longitudinal splits of the upper side which is so covered with pollengrains. A small pistill with a shrivelled up stigma is embraced by the hollowed bases of the two stamina. The folded up lamina of the transformed anther offer consequently here the only landing place for approaching insects. By pushing against them from above with a short hair or by the tread of an insect upon them (as I have sometimes observed it with Tipula,7 the only insects now in my room) the two anthers hitherto united spring asunder with an elastic impulse so that in the lapse of about 1 second the transformed anther sweep through about 60 degrees and is pressed against the lower sepal, whilst in the same time the upper turns upwards through about 30 degrees and puts itself in a horizontal position or slightly bent upwards. The hair with which I tried was in every case laid on with pollen grains

Insects which by their flying on cause that elastic springing asunder, are certainly laid on with pollen at their legs or at their underside and when they land then on the pistill of a female flower, part of that pollen will indubitably remain sticking at the prominent stigma

[Enclosure]

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Larson, James L. 1971. Reason and experience. The representation of natural order in the work of Carl von Linné. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Sprengel, Christian Konrad. 1793. Das entdeckte Geheimniss der Natur im Bau und in der Befruchtung der Blumen. Berlin: Friedrich Vieweg.

Stafleu, Frans Antonie. 1971. Linnaeus and the Linnaeans. The spreading of their ideas in systematic botany, 1735–1789. Utrecht: A. Oosthoek for the International Association for Plant Taxonomy.

Summary

The Origin converted him from a Linnean interpretation of flowers and mosses.

Glad that CD appreciates his continuing work on mosses, in support of natural selection.

Plans to repeat CD’s orchid experiments.

Sends interpretation of the floral anatomy of Lopezia miniata.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-5457

- From

- Heinrich Ludwig Hermann (Hermann) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Lippstadt

- Source of text

- DAR 171: 290, 290/1

- Physical description

- ALS 5pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 5457,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-5457.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 15