In 1879, Darwin continued his research on movement in plants and researched, wrote, and published a short biography of his grandfather Erasmus Darwin as an introduction to a translation of an essay by Ernst Krause on Erasmus’s scientific work. Darwin’s son Francis spent a second summer at the Botanical Institute in Würzburg, Germany, learning the latest experimental techniques in plant physiology. As well as their regular tour of visits to family, the Darwins spent most of August on holiday in the Lake District. In October, Darwin’s youngest son, Horace, became officially engaged to Ida Farrer, after some initial resistance from her father, who, although an admirer of Charles Darwin, thought Horace a poor prospect for his daughter.

The transcripts and footnotes of over 640 letters written to and from Darwin in 1879 are now online. Read more about Darwin's life in 1879 and see a full list of the letters.

Highlights from the 1879 letters include:

Your praise of the life of Dr D. has pleased me exceedingly, for I despised my work & thought myself a perfect fool to have undertaken such a job. (Letter to J. D. Hooker, 1 December [1879])

In early 1879, as a tribute on Darwin’s 70th birthday, the editor of the German periodical Kosmos, Ernst Krause, published a short account of the scientific work of Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. Darwin asked for permission to publish an English translation of it, and then decided to write his own biographical preface, based on sources available within his own family. The project grew until the preface was longer than the translated article. Darwin contacted cousins, sent his sons to search archives, and hired a genealogist. The strain of writing history rather than science told severely on him, and in the end the proof-sheets were edited by his daughter Henrietta. The result was an entertaining little book, with low but respectable sales, and Darwin was relieved to hear that his friends approved of it.

let me advise you strongly to invest in safe securities paying low interest. By this plan my father died a rich man. ... Trust to common sense & not to professional advisors. (Letter to the Darwin children, 21 February 1879)

Just over a week after his birthday, Darwin announced that he had decided to divide his surplus income annually among his seven children, who he thought were ‘all very sensible & steady’, although not so much so as not to require some sound financial advice. His eldest son, William, a banker himself, responded with gratitude, adding, ‘I shall certainly save it myself as these last Banking troubles show the necessity for Bankers to have larger private reserves in available securities.’

I have no shade of doubt that the apex is a kind of brain for certain movements, like the gland of Drosera for inflection—or the hairs on Dionæa—ie a specialised centre for receiving certain irritations (Letter to Francis Darwin, 2 July [1879])

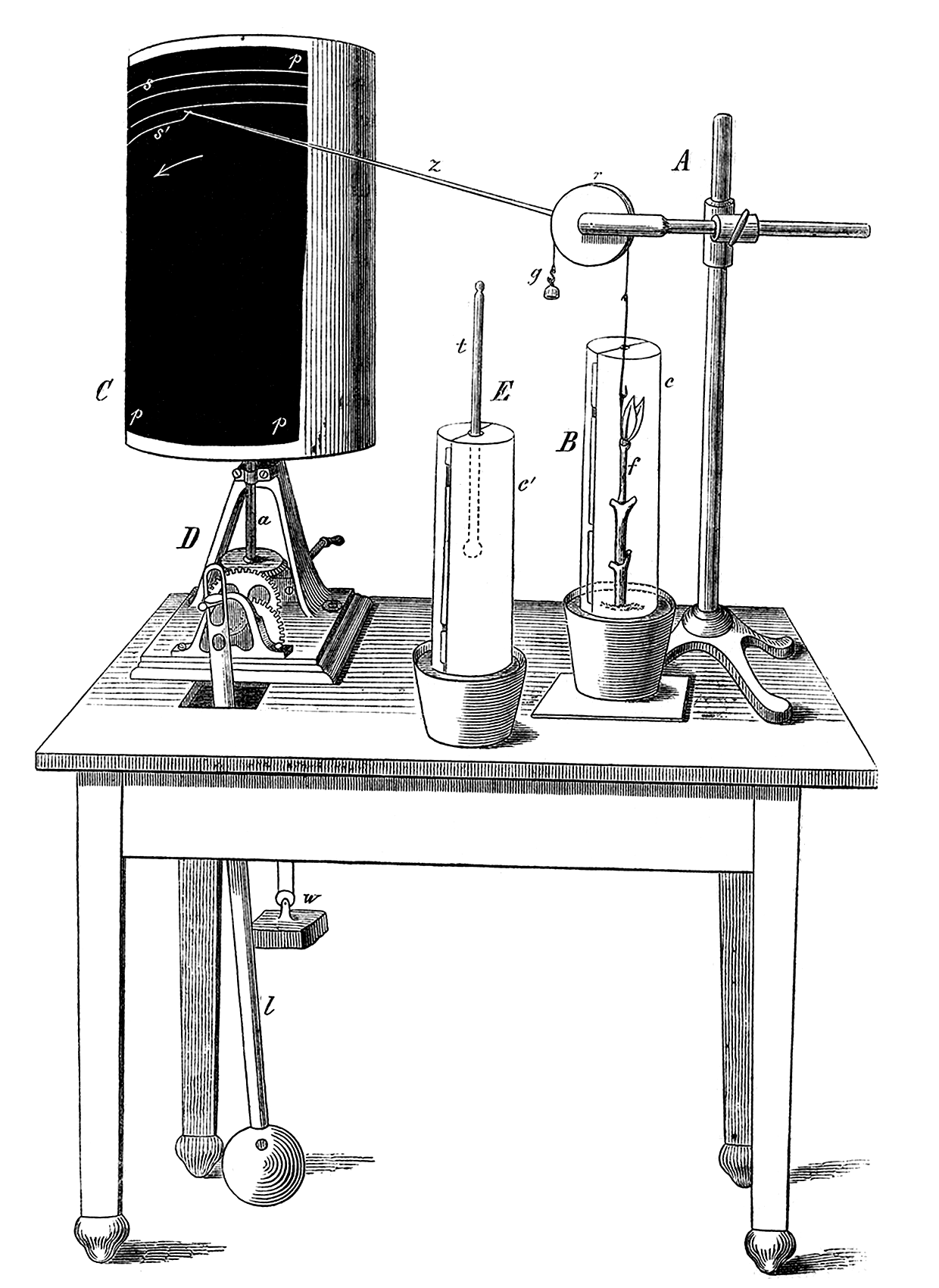

Darwin regarded his continuing experiments on movement in plants—in this case, in root-tips—as his real work of the year. His son Francis spent three months at Julius Sachs’s botanical laboratory in Würzburg, Germany, working on the same problems. This volume contains many letters between father and son about their respective research, and about the difficult academic politics of Würzburg.

What a pity there cannot be 2 sets of men in our Government,—one to do all the miserable squabbling & the other to attend to the real interests of the country. (Letter to T. H. Farrer, 23 October 1879)

During the year Darwin continued his support for other workers in science. At the urging of Arabella Buckley, he floated the idea of a pension for Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer of the theory of natural selection. Nothing came of it in 1879, but it was to bear fruit later. He sent £100 to a German palaeontologist, Leopold Würtenberger. He also continued to try to secure government support for James Torbitt’s efforts to breed blight-resistant potatoes, with the help of Thomas Farrer, who was permanent secretary at the Board of Trade. Progress, however, was frustratingly slow; the minds of the politicians seemed to be elsewhere.

Horace has as sweet a temper & as unselfish a disposition as anyone whom I have ever known; & this is of more importance for the happiness of married life than wealth, grandeur or distinction, & more even than strong health. (Letter to T. H. Farrer, 13 October 1879)

Darwin wrote this to his son Horace’s future father-in-law, Thomas Henry Farrer, in October, after Farrer had given up his opposition to the match between his daughter, Ida, and Horace. The two families had known each other for a long time, and Farrer’s opposition, on the grounds of Horace’s poor health and lack of career, came as a shock to the Darwins. Darwin himself was called upon to intercede. In the end, Farrer was won round, and the wedding was planned for early 1880.