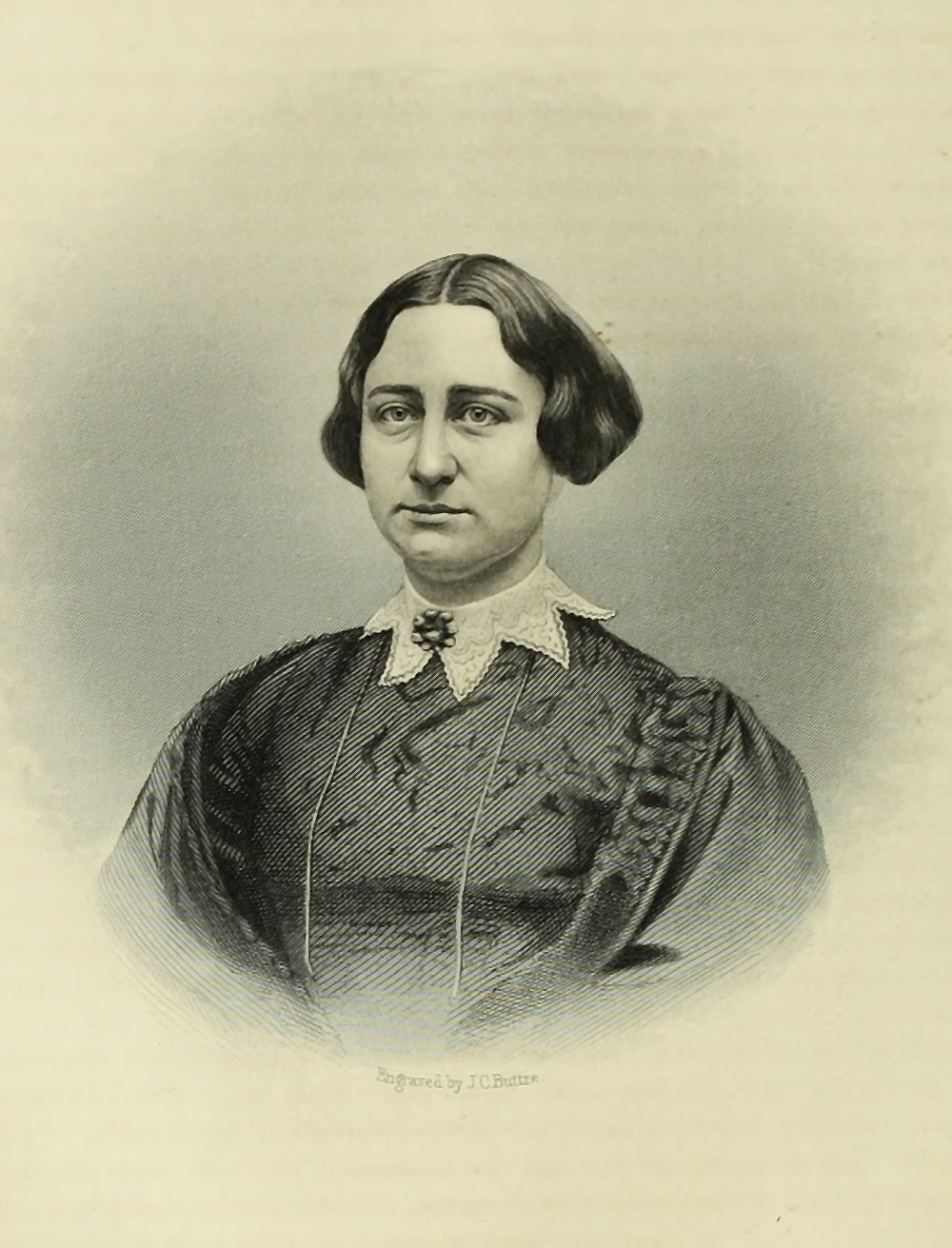

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (1825–1921) was born in Henrietta, New York. In early life she began to preach in her local Congregational Church and went on to teach. Throughout her life she was a renowned public speaker, a vociferous social reformer and promoter of women’s rights. She was the first woman to be ordained as a minister in the United States. Brown later became a Unitarian and remained committed to the idea of that women’s participation in religion could improve their status in society. She was also a keen philosopher and scientist who, like Lydia Becker, published scientific works and corresponded with Charles Darwin.

The achievements of women like Blackwell and Becker should not be underestimated; at a time when science was deemed a gentlemanly pursuit reserved for the so-called “rational sex”, they were part of a select group of women who broke the trammels and defied gender ideology in order to participate in the masculine world of science.[1] In this way Blackwell’s and Becker’s science embodied their politics; they attempted to eradicate inequality and make a masculine pursuit sexless and universal.

In real terms, however, Becker and Blackwell were far from the equals of Darwin and his male corespondents. Denied access to formal scientific education and refused membership of formal societies, women scientists existed somewhere on the periphery of the world of institutional science. While Becker and Blackwell were able to access the world of science through the private and appropriately feminine channel of letter-writing, their involvement in the public world of science was severely limited by dominant gender ideology which celebrated women as moral and feeling but ultimately irrational and thus destined by their nature to be domestic, nurturing creatures.

The notion of the private, domestic middle class woman was so pervasive in nineteenth-century Britain that scientific women often felt compelled to publish their works anonymously; Becker’s 1864 publication Botany for Novices , for example, was published under her initials, a strategy which - alongside her detached narrative and deliberate use of gentlemanly discourse – left her work free from any suggestion that it might have been produced by a woman.

Darwin’s letters suggest that while he was open to the concept of women being involved in the world of science (he relied heavily on women observers, for example), his default position was that science and scientific correspondence was the preserve of men. Thus, when Antoinette Brown Blackwell sent a copy of her Studies in General Science to Darwin in 1869, he assumed from its content and subject matter that its author – “A. B. Blackwell” – was male; “Dear Sir,” Darwin wrote in reply, “I am much obliged to you for your kindness in sending me your “Studies in General Science”, over which, as I observe in the Preface, you have spent so much time.”

[1] For a discussion of the so-called “masculinisation” of science - particularly botany – in the nineteenth century see A. Schteir, Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science, (John Hopkins University Press, 1999).