From B. D. Walsh 7 November 1864

Rock Island, Illinois, U.S.

Nov. 7. 1864

Chas. Darwin Esq.

Dear Sir,

Your welcome letter of Oct. 21 was received two days ago.1 I transmit you by this Mail a Paper of mine on “Certain Entomological Speculations of the New England Naturalists”, in which I have taken occasion to show the absurdity of Agassiz’s refutation of the “Origin of Species”.2 Since it was published, I have received a long letter of seven pages of letter-paper from Alex. Agassiz, criticizing in a friendly way sundry passages in it.3 Amongst other things, he observes in regard to my charge that Prof. Agassiz had misstated your theory, that “Darwin in a recent letter to father thanks him for the manner in which he has conducted his opposition to his theory.4 So you see that opinions may differ on the misstatement of Darwin’s Theory”. In reply, I suggested that that fact merely showed that having been abused as an atheist, deist, infidel &c by other writers, you probably felt grateful to any writer who was willing to allow you “a spirit quite as reverential as his own”. (Meth. Study Pref. p. iv.)5

I cannot resist the temptation of quoting the sentiments of a botanical friend of mine,6 to whom I had written that I was about to enter a plea in the great case of Agassiz. vs. Darwin,—“I hope you will give Agassiz a thorough blowing up. It may do some young naturalists good; but as for your penetrating the sublime self-complacency of the great I Am & disturbing his infallible theories, that is another matter. I cannot be so lenient as you are even—to attribute his course of argument to a mind so illogical that he cannot educe a correct conclusion. It is wilful, mean pettifogging—taking hold of every trivial thing that can be twisted into a fancied support of his position—& knowingly ignoring the most patent truths (that of themselves need but be stated to grind his deductions to powder) in a way that is insulting to a person of decent intelligence”.

I do not know what the European Scientific World thinks of Agassiz, but here he is popularly considered as the incarnation of Science & as infallible as the Bible.7 He strikes me as a very much overrated man, who perpetually allows his imagination to get the better of his judgement, & who not unfrequently argues for victory instead of for truth. I have heard him myself in a Public Lecture8 assert in the most unqualified manner as a notorious truth that all the animals of every Geological Epoch were specifically distinct from those of the Epochs preceding & following it & that in the Eocene, Miocene &c periods there merely began to be some approximation to the present order of things. I am told by a New England correspondent,9 who belongs to his School, that he positively denies the truth of the facts upon which the very names Eocene &c are based. Do any European authorities uphold him in these views? I am told Pictet does.10

You ask, “What can be the meaning or use of the great diversity of the external generative organs” in many groups of Insects?11 I don’t know that I can completely explain this matter, which has long occupied my attention, but I can quote you a few facts which throw some little light on it.

1st. In all the Agrionidæ & Libellulidæ, as you are doubtless aware, after the ♂ has embraced the neck of the ♀ with his caudal forceps, no copulation can possibly take place unless the ♀ voluntarily curves her abdomen downwards & forwards so as to meet the ♂ penis. 12 I conceive that the various thorns, tubercles, incurvings & excurvings which we find on the ♂ caudal forceps are so many different appliances for enciting the amorous passions of the ♀ & inducing her to curve her abdomen in the manner necessary to accomplish the coitus. In both sexes of many species, when they are roughly handled after capture, the abdomen is frequently curved downwards in a similar manner, which I suppose originated the English name of “Horse-stingers”. I conceive that a puncture from one of the sharp thorns found on the caudal ♂ forceps of many species would operate in the same manner, & that the first individual that had such a thorn gained an advantage in his amours over his thornless compeers. I have often watched the united sexes careering backwards & forwards for a long time without the ♀ consenting to the coitus.—

2nd. You must often have noticed how repeatedly the ♂ butterfly in many species strikes in the air at the ♀ without effectuating a connection. A very slight change in the shape or armature of his forceps might enable him to sieze the ♀ genitals more readily, & gain an advantage over other ♂ ♂.—

3rdly Simple as the coitus of insects appears, there are four distinct modes in which it is effected. 1st. The normal mode, where the ♂ abdomen squarely surmounts the ♀ abdomen, the ♂ tip curving slightly downwards & the ♀ tip slightly upwards. 2nd. Where the ♂ surmounts the ♀ in the usual manner, but slips the tip of his abdomen sideways under that of the ♀, the penis being erected vertically—

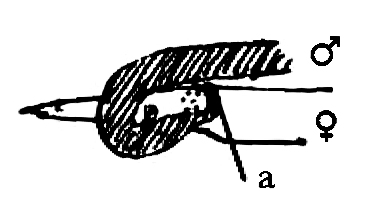

Years ago in England I observed this was the method in the Nepidous genus Ranatra, & I observe it here in Perla & its allies. 3rd. Where the ♂ surmounts the ♀ in the usual manner but curves the tip of his abdomen downwards & forwards by the side of ♀ abdomen, so as to embrace the entire abdomen of the ♀ forward of the vulva, with the caudal forceps a, thus bringing ♂ ♀ genitals into contact,

I observe this method in the Phasmide genus Diapheromera. 4th The well-know coitus of Agrionidæ & Libellulidæ.— There may be other modes which I have not noticed, but these are sufficient to show that there is a great diversity in the mode in which the coitus of insects is effected, & in almost every case the structure of the parts is such that the ♀ can, if she chooses, refuse coition. Hence I conceive has arisen the great variation in the structure & armature of the ♂ organs.

You express a desire to know what my life in this new country is. I will, at the risk of boring you, give you the particulars. When I left England in 1838, I was possessed with an absurd notion that I would live a perfectly natural life, independent of the whole world—in meipso totus teres atque rotundus.13 So I bought several hundred acres of wild land in the wilderness, 20 miles from any settlement that you would call even a village, & with only a single neighbor. There I gradually opened a farm, working myself like a horse day after day, & raising great quantities of hogs & bullocks. Being far away from any mechanics, & having the natural gift of turning my hand to almost anything except blacksmithing, I did all kinds of jobs for myself, from mending a pair of boots to hooping a barrel or putting a new head into it, for the simple reason that it was less trouble to do such work myself than to hitch up my team & drive 10 or 20 miles to a mechanic’s. I suppose I should at this present moment be vegetating there like a cabbage, but there was a Swedish Colony that settled in the neighborhood14 & dammed up the river everywhere for mill-seats, so that a great deal of malaria was generated & I had some severe attacks of fever, one of which brought me almost to death’s door. So at the end of 12 years I sold out at a great sacrifice, & found that I was just $1000 poorer than when I began. I then moved to Rock Island15 & went into the Lumber business—“lumber” in America means all kinds of sawed boards & planks, “timber” being stuff that is hewed with the broad axe—& in seven years time had made a good many thousand dollars. I then, thinking I had been a slave about long enough, quitted that business, & invested most of my funds in building ten two-story brick houses for rent, upon the proceeds of which & a few of Uncle Sam’s Bonds, I manage to live & keep all the time out of debt. If the times were what they used to be, I should have my whole time to myself & as large an income as I care about. As it is, what with the depreciation of such property & what with the war-taxes &c,16 I have to devote about of my time to executing sundry repairs on my tenements, & the remaining I devote to Entomology. I suppose I have the largest collection of Insects in America, except one or two in the great Atlantic Cities.17

Will you favour me with your Photograph, & if convenient Prof. Westwood’s,18 for my Entomological Album? I enclose you my own.

Believe me, my dear Sir, | very sincerely yours | Benj. D. Walsh

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Columbia gazetteer of the world: The Columbia gazetteer of the world. Edited by Saul B. Cohen. 3 vols. New York: Columbia University Press. 1998.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

DAB: Dictionary of American biography. Under the auspices of the American Council of Learned Societies. 20 vols., index, and 10 supplements. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons; Simon & Schuster Macmillan. London: Oxford University Press; Humphrey Milford. 1928–95.

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

Dupree, Anderson Hunter. 1959. Asa Gray, 1810–1888. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Lurie, Edward. 1960. Louis Agassiz: a life in science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McPherson, James M. 1988. Battle cry of freedom: the Civil War era. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marcou, Jules. 1896. Life, letters, and works of Louis Agassiz. 2 vols. London and New York: Macmillan and Co.

Marginalia: Charles Darwin’s marginalia. Edited by Mario A. Di Gregorio with the assistance of Nicholas W. Gill. Vol. 1. New York and London: Garland Publishing. 1990.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Sorensen, W. Conner. 1995. Brethren of the net. American entomology, 1840–1880. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press.

Walsh, Benjamin Dann. 1862a. List of the Pseudoneuroptera of Illinois contained in the cabinet of the writer, with descriptions of over forty new species, and notes on their structural affinities. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (1862), pp. 361–402.

Winsor, Mary Pickard. 1991. Reading the shape of nature. Comparative zoology at the Agassiz museum. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Summary

Notes Louis Agassiz’s opinions on CD’s views.

Mating and sexual organs of insects.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-4663

- From

- Benjamin Dann Walsh

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Rock Island, Ill.

- Source of text

- DAR 181: 10

- Physical description

- ALS 4pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4663,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4663.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 12