From Alexander Agassiz [before 1 June 1871]1

Museum of Comparative Zoology, | At Harvard College, | Cambridge, Mass.

My dear Mr. Darwin

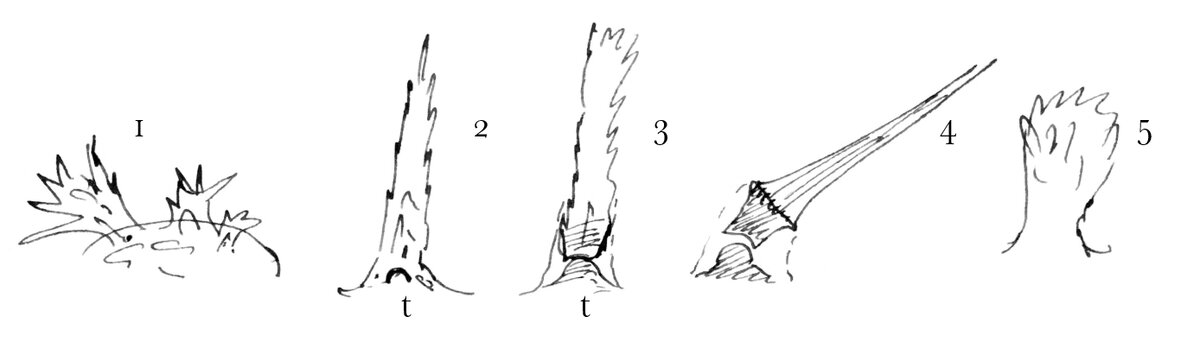

There are some points in the sexual differences of Viviparous fishes from California (Embiotocoids) which are suggested to me by reading your chapters on sexual selection The males and females can be distinguished at a glance by their anal fins. In some genera the shape of the fins even is different in the two sexes, viz in Amphyticus, Metrogaster, Holcenotus, & Hysterocarpus—while in the other genera of the family Micrometrus, Hyperprosopon, Phanerodon, Rhachochilus, Embiotoca, the fins (anal) in the two sexes are similar in shape, but we find invariably in the males a fleshy accumulation near the base of the anal while the anal fins of the females are perfectly smooth.2 In the genera first mentioned this fleshy accumulation is placed in the central part of the fin, what the use of this is I cannot say. It is found in small specimens already and does not appear simply at breeding season. The accompanying sketch shows this better than any description I can give. How the impregnation takes place in these fishes I do not know and no fisherman in San Francisco ever could give me any information on the subject3 There must evidently from the nature of the case be copulation yet the males have no copulative organ and no means of retaining the sperm near the sexual openings except this fleshy accumulation on the anal fin which may perhaps serve some such purpose in the process of fecundating the females, though how the sperm reaches the eggs I cannot imagine as the eggs when immature are far up in the ovarian bag, at a considerable distance from the sexual opening, to preserve the young and prevent the disappearance of the species? the small number of young rarely over 18—are retained in the pouch of the female and leave it only as full fledged, scaly fishes, frequently as long as the mother. There is apparently but one breeding season in the year & the species would soon die out, were the 18 or less eggs which come to maturity left to float about at the mercy of the winds & waves and take their chance of becoming impregnated & afterwards to grow to maturity. The amount of milt of one of the males is quite considerable entirely out of proportion to the number of eggs to be fecundated & as far as my experience with the fishermen & in the San Francisco market went there is not a larger number of females than of males.

One other point suggested by some remarks made by Mivart in his Genesis of Species.4 He seems to look upon the pedicellaria as such inexplicable organs Müller and I have both conclusively shown that pedicellariae are modified spines.5 Their development as far as I have seen it in Starfishes and in Seaurchins leaves no doubt on this point. & their function in the Seaurchins at least in those where they are most highly developed & exist in greatest numbers is that of Scavengers they keep the ambulacral suckers free from any impurities which may become entangled in the ambulacral spaces, and have found their way there either as excrements from the apex or have been brought there by currents. & it is a very amusing sight to see the rapidity with which these small forceps will work and clear away any rubbish which comes in their way & throw it off the Test of the Seaurchin, passing it from one forcep to the other. It is as early a sign of intelligence as I have noticed in lower animals except the case of maternal sollicitude displayed by a Starfish for its eggs.6

We are progressing finely with the addition to our Museum, father I am happy to say is gaining daily in strength.7 The doctors advise him to absent himself for some time from Cambridge to ensure his total recovery and he talks of making a trip to California via Cape Horn! in one of the Government Vessels, which is to be supplied with means for deep sea dredging on the way.8

With kindest remembrances for Mrs Darwin from Mrs Agassiz to yourself & the members of your household | I am always | very truly yours | Alex. Agassiz

[Enclosure]9

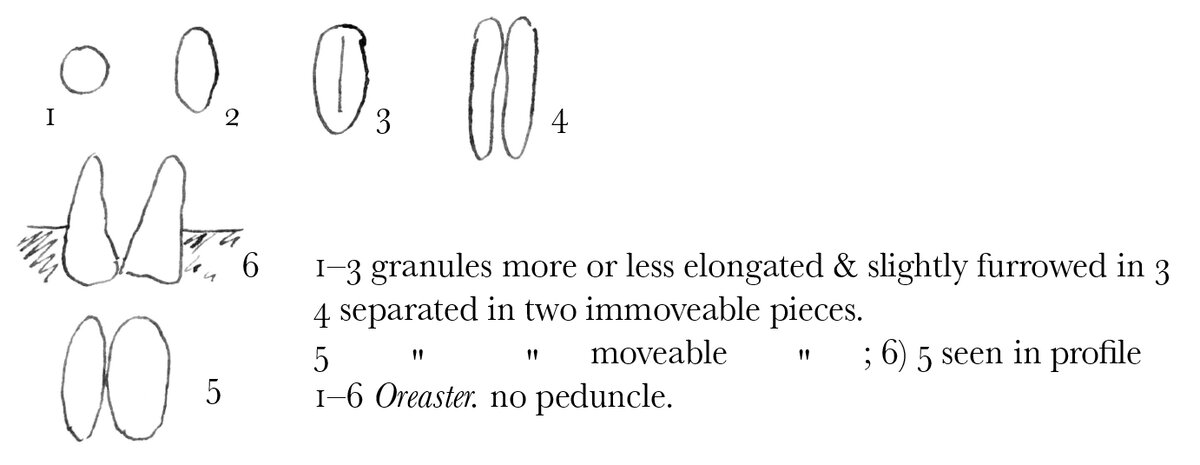

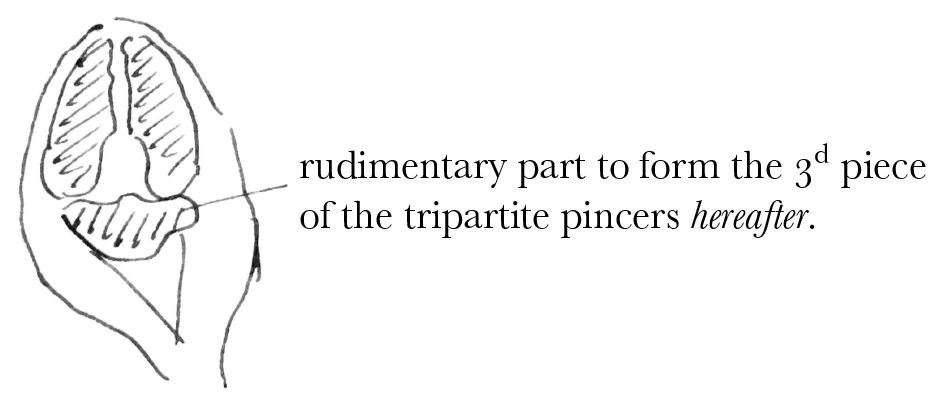

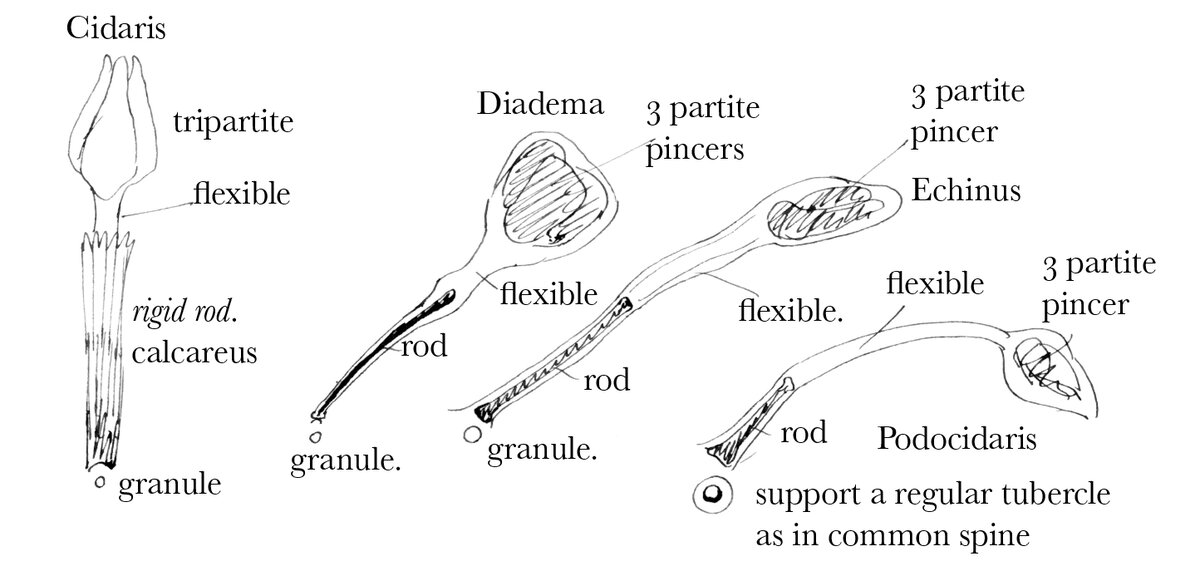

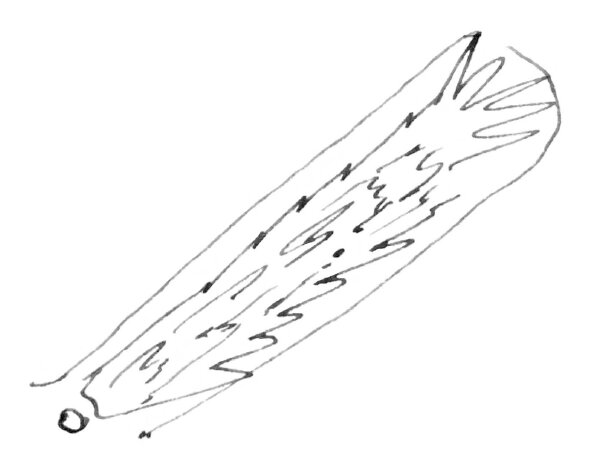

Pedicellariae with tripartite pincers are found in all Seaurchins In Starfishes we find not only pedicellariae with tripartite pincers (Luidia) but also pedicellariae in which one of the forceps is reduced to a support of the other two. (Asteracanthion); while in other genera there are the so called valvular pedicellariae (Oreaster, Astrogonium) in which the two pincers alone exist.10 We have all possible gradations between what are called simple granules+ in such genera as Oreaster to the valvular pedicellariae of the same genus to the tripartite pincers with one rudimentary member of Asteracanthion, to the genuine tripartite pincers of Luidia ressembling the tripartite pedicellariae of Echinidae but unlike them not provided with a moveable stem; but merely perched upon a support. Some of the pedicellariae of Asteacanthion are already provided with a short muscular stem but not a calcareous one In regular Echini we find the tripartite peddicellariae supported upon a stem with a calcareus rod inside and capable of motion very much like that of the ordinary spines11 This calcareus rod+ is articulated generally upon a miliary tubercle (a simple granule) analogous to that of the spines, but in one of the genera dredged by Mr Pourtales, Podocidaris I found pedicellariae articulated upon a tubercle provided with a mamelon a scuticular circle in all respects similar to that of the ordinary spine of the Seaurchin.12 In the Spatangoids13 we find what are called fascioles bands of minute granules supporting embryonic spines articulated upon these bands limited to certain regions of the body performing the functions of regular pedicellariae of keeping the dirt from the ambulacral petals, and at same time they are provided with tripartite pedicellariae more complicated & more highly organized than in any other Echinoderms, scattered irregularly over the test. In our common Sea urchin the pedicellariae (Toxopneustes drobachiensis)14 are used to remove the dirt from the test & keep it from getting among the suckers. We never find strictly branching spines among Echini we have nothing more than very long spines sometimes equalling the diam of the main spine though in very young Seaurchins it would often be difficult to say they were not for their fantastic shape.

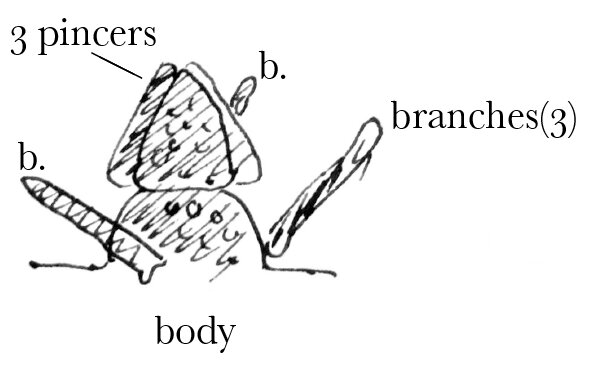

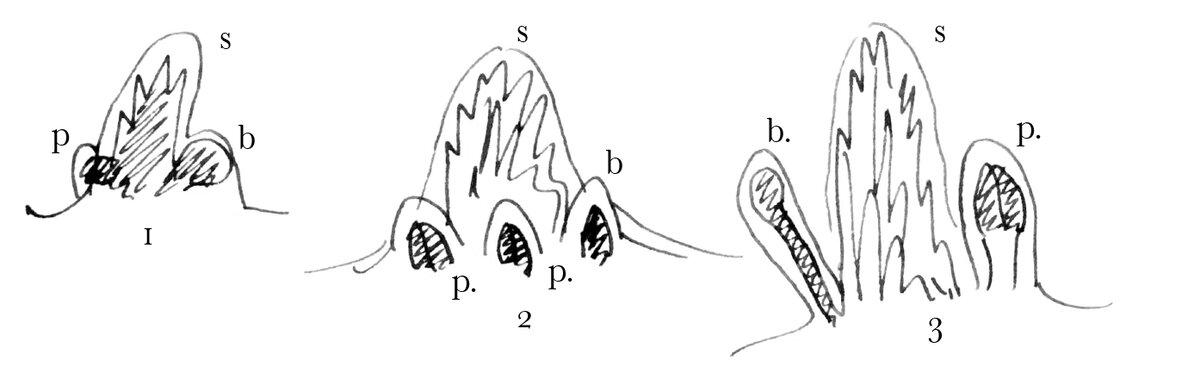

But we do have in Starfishes in the genus Luidia the very combinations needed to shew that the pedicellariae are only a modified branching spines we have a central prolongation of the fixed spine and around this are placed the three pincers of the body sometimes even with a second set of them at base of the spine. The following rough sketches will shew you the whole argument better than my description.

Asteracanthion with a short flexible stem (muscular

Luidia

immoveable base pincers can simply open & shut

Same structure as previous one in Luidia. but the spine nature is more apparent 3 branches at base of immovable support of tripartite pincers.

Going backward a little you will see that we find all possible variation between the pedicellariae of Starfishes and hooks, of Ophiurans.15 and in same way all possible gradations between the pedicellariae of Seaurchins and the anchors and plates on the dermal portion of Holothurians,16 & all these calcareus deposits are modified spines highly specialised in Echinidae as prehensile organs. Their early development is the same of all these bodies as accumulations of lime cells rising above the general level, covered by a layer of epithelial, and this goes on till a fixed spine is formed. as is still found in some genera of Echinidae (both fixed & moveable exist on it) viz. Podocidaris and Glyptocidaris (a fossil of Jurassic period)17 or else it develops a joint & forms the usual spine of the Seaurchin or it is developed into the fixed pedicellariae of Starfishes or the moveable ones of Echini with jointed stems.

1 piece of test of seaurchin with very young spines fixed.

2 older. spine still fixed tubercle appears .t.

3 connection between tubercle of spine very slight. older than 3.

4 full sized spine with bossed ring striated longitudinally in all former figures spines made up of larger or smaller cells more or less packed closely according to age.

5 is a fixed spine like 2 in structure found in an adult Seaurchin Podocidaris from deep water off Florida.

Spines like 3. with an imperfect articulation are characteristic of the spines found on the scaly buccal membrane of Cidaridae, something similar also in the old Silurian Palechinidae.18

outline represents epithelial layer.

1. 2. 3. different stages of growth of spines of pedicellariae & branch of spine of our common Starfish Asteracanthion berylinus19

s spine

p pedicellariae

b branch of spine

Embryonic spine of the fascioles of Spatangoids

+This point I have never pressed sufficiently but am convinced from the similar mode development of granules, pedicellariae, spines of the correctness of the statement in Starfishes and Seaurchins—

+In all the Cidaridae this rod is less moveable still recalls somewhat the structure of pedicellariae of Starfishes

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Agassiz, Alexander. 1864. Embryology of the starfish. From J. L. R. Agassiz’s Contributions to the Natural History of the United States vol. 5, published 1877. Cambridge, Mass.: n.p.

Agassiz, Alexander. 1873. The homologies of pedicellariae. American Naturalist 7: 398–406.

Agassiz, Louis. 1853. Extraordinary fishes from California, constituting a new family. American Journal of Science and Arts 2d ser. 16: 380–90.

Hubbs, Carl L. 1917. The breeding habits of the viviparus perch, Cymatogaster. Copeia (1917): 72–4.

Lurie, Edward. 1960. Louis Agassiz: a life in science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marginalia: Charles Darwin’s marginalia. Edited by Mario A. Di Gregorio with the assistance of Nicholas W. Gill. Vol. 1. New York and London: Garland Publishing. 1990.

Origin 6th ed.: The origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 6th edition, with additions and corrections. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1872.

Salter, John William. 1857. On some new Palæozoic star-fishes. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 2d ser. 20: 321–334.

Tarp, Fred Harald. 1952. Fish Bulletin No. 88. A Revision of the Family Embiotocidae (The Surfperches). UC San Diego: Scripps Institution of Oceanography Library.

Summary

Instances of sexual differences in viviparous fishes, suggested by reading chapters on sexual selection [in Descent] and by Mivart’s Genesis of species.

Notes on echinoderms.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-7415

- From

- Alexander Agassiz

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard

- Source of text

- DAR 69: A43–6 DAR 89: 29–31

- Physical description

- ALS 8pp † sketches

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 7415,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-7415.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 19