From Fritz Müller 1 January 1867

Desterro, Brazil,

January 1th 1867.

My dear Sir

In my last letter (Decbr. 1th) I told you that Oncidium flexuosum is sterile with own pollen; more than 80 flowers of 8 plants, which were fertilized with own pollen (taken either from the same flower of from a distinct flower of the same panicle or from a distinct panicle of the same plant) yielded not a single seed-capsule; the flowers fell off about a week after fertilization.— But what is still more curious, pollen and stigma of the same plant are not only entirely useless to, but even act as a poison to each other!1 Thus, four or five days after fertilization a brownish colour appears on the adjoining surface of the pollen and stigma and soon afterwards the whole pollinium is rendered dark-brown.2

This is not the case when you bring instead of own pollen, the pollen of widely different species on the stigma of Oncidium flexuosum. Among others I tried the pollinia of Epidendrum Zebra3 (nearly allied to, or perhaps not specifically distinct from Ep. variegatum).4 Of course no seed-capsules were produced; 8–9 days (in one out of about 20 flowers 12 days) after fertilization the germs began to shrink, but even then the pollen and its tubes which sometimes had penetrated in the upper part of the germ, had a perfectly fresh appearance, rarely showing a very faint scarcely perceptible brownish colour.— The pollinia of Ep. fragrans also I found to be perfectly fresh, as well as their tubes after 5 days stay in the stigmatic chamber of Oncidium flexuosum.

The poisonous action of own pollen becomes still more evident, on placing on the same stigma two different pollen-masses. In a flower of Oncidium flexuosum, on the stigma of which I had placed one own pollen-mass and one of a distinct plant of the species, I found five days after the former brown, the latter fresh; in some other flowers 4 or 5 days after both the pollen-masses were brown, and I think, although my experiments are not yet quite decisive, that own pollen will always kill the pollen of another plant when placed on the same stigma.— Now compare this destructive action of own pollen with that of Epidendrum (species allied to variegatum).

Debr. 15 I placed on the stigmas of some flowers of Onc. flexuosum one pollen-mass from a distinct plant of that species and one of Epidendrum.— Debr. 21th both the pollen-masses fresh melting with numerous tubes.— Dec. 26 both the pollen-masses dissolved into single pollen-grains, most of which have long tubes; numerous tubes of either pollen descend half way down the germen; the pollen-mass of Epidendrum is to be reconnoitred only by the unaltered caudicula. Dec. 30 the germs of the two resting flowers (all the others having been dissected) are slightly curved to one side; this side, probably that of the Ep.-pollen swelling to a lesser degree than the other.5

I suspect that the sterility with the same plants pollen will be very common among Vandeae and one of the principal causes of them seeding so badly; for the several specimens of most of these plants grow scattered in the forests, at great distance from one another and thus the chance of pollinia being brought from a distinct plant is not very great.6

I already observed a second instance of this sterility, and of the mutual poisonous action of the same plants pollen and stigma. I found a large raceme of a Notylia with more than sixty aromatic flowers. The slit lending to the stigmatic chamber is less narrow in this second species than in that mentioned in one of my former letters and a single pollen-mass might be introduced rather easily.7 I fertilized (Dec. 12th 13th 14th) almost all the flowers with pollen from the same raceme. Two days after fertilization the flowers withered and I found that the pollen-masses were dark brown and had not emitted a single tube. You see the poisonous action of own pollen is here much more rapid, than in Oncid. flexuosum. There remained eight flowers, which had not been fertilized, and these I fertilized (Decbr. 19th 20th) with pollen-masses from a small raceme of a different plant of the species. Two of them I afterwards dissected and found the pollen fresh and having emitted numerous tubes. The other six have now fine swelling pods.8

Very different from the innocent pollen of Ep. Zebra, that of Notylia is as deletery to Oncidium flexuosum as are this latter plants own pollinia. Dec. 14 I placed on the same stigma of Oncidium flexuosum one pollen-mass from a distinct plant of that species and one of Notylia. Decbr. 21: the latter was brown as well as the neighbouring part of the stigma; the Oncidium pollen-mass was nearly fresh; only on the side towards the Notylia-pollen a brownish stripe began to make its appearance between pollen-mass and stigma.9

Strange as the destructive action of own pollen may appear, it may be easily shown to be of real use to the plant. If flowers are sterile with own pollen and if the introduction of own pollen-masses into the stigmatic chamber prevents, as it does in Oncidium and Notylia the subsequent fertilization by other pollinia, it must be injurious to the plant to waste anything in the nutrition of flowers rendered useless by the introduction of own pollinia, and useful to become rid of them as soon as possible.10 This view is confirmed by a comparison of Oncidium and Notylia. Decbr. 21th I fertilized on a panicle of Oncidium flexuosum 36 flowers (12 with own pollen, 24 with pollen from a distinct plant). Decbr. 24th before any difference had appeared between the two kinds of pollen the peduncles and germs of 55 not fertilized flowers of this panicle were withering and discoloured yellowish, while all the fertilized flowers had green swelling germens. The panicle had about 160 flowers.

In Notylia on the contrary, when about of the flowers of a raceme were fertilized with own pollen, they all fell off in a few days without injuring even one of the not fertilized flowers. In Notylia fertilization is much easily effected a week or so after the expansion of the flowers, the entrance of the stigmatic cavity being open.

As to Notylia I may add that nectar is secreted at the base of the bracteae and also at the base of the upper sepalon. I found nectar at the base of the bracteae in a small species of Oncidium also.11

At last I have gratified my wish of examining myself the wonderful genus Catasetum.12 I had three fine racemes of the male Catasetum mentosum and one raceme with only three flowers of Monachanthus (probably of the same species).13 In this Catasetum a membrane connects the antennae with the interior margin of the stigmatic chamber. The ovula are scarcely more rudimentary than in Monachanthus, and not so much so, as in many other Vandeae. The stigmatic surface is not viscid at all; but notwithstanding pollen-masses (from the same as well as from a distinct plant and also from Cattleya Leopoldi), when introduced, began to dissolve into groups of pollen grains and to emit tubes, some of which were 2mm long, … the flowers withered.—14

The female flowers, of a uniform green colour, are much like those of Monachanthus viridis, but the anther is much smaller. There is a pedicellus and disk; the disk is brown, and quite dry; the pedicellus white, elastic, not connected with the pollen-masses! On touching it, the pedicellus is ejected at some distance assuming the form of a hemicylinder.15 The anthers do not open (at least they had not done so some days after the expansion of the flowers, long after the pedicelli having been ejected). The pollen-masses consequently remain enclosed; although being much smaller, they ressembled in shape those of Catasetum and had a small caudiculus. I brought three of these pollen-masses into the stigmatic chamber of Catasetum, where they emitted numerous pollen-tubes. Infortunately I had cut off the raceme of Catasetum, in order to preserve it from insects, and thus I am unable to say whether the pollen of Monachanthus may as yet be able to fertilize the ovules of Catasetum.— Certainly insects can never effect this fertilization. At all events this seems to me to be one of the most interesting cases of rudimentary organs. We have on the one hand in Monachanthus a disk, a well developed elastic pedicellus, caudiculi and apparently good pollen, we have on the other hand in Catasetum a stigmatic surface able to cause this pollen to emit its tubes, and apparently good ovules and in spite of all this—from the dryness of the stigma and disk and from the pedicelles not connected with the enclosed pollen-masses an utter impossibility of fertilization.16

When the pollen-masses of Catasetum are introduced into the entrance of the stigmatic cavity of Monachanthus, they peep out at half their length; but in the course of the first days they are allowed, as it were, entirely, and the stigma is shut. This swallowing of the pollen-masses is also to be observed in Cirrhaea and here it is easy to see how it is effected. The stigmatic cavity has a very narrow transversal slit into which only the very tip of the long pollen-masses may be introduced. Under the slit the cavity widens gradually and continues into a large canal occupying the center of the columna; this canal is empty, while the upper part of the stigmatic cavity is filled with loose viscid cells. Now the tip of the pollen-masses in contact with the humid stigma swells and thus is forced down into the wider inferior part of the stigmatic cavity and at last into the canal of the columna. Of course, what at first sight appears contradictory, the thickest pollen-masses must be swallowed first. Thus Decbr. 25th at 7h in the morning I fertilized two flowers of Cirrhaea with dry pollen-masses of another plant of the species (collected Decbr. 3d), four flowers of the same raceme with fresh own pollen-masses and one flower with a much larger pollen-mass of Gongora (bufonia?).17 This latter had disappeared at 3h in the afternoon, when the others peeped out half their length; at 7h in the evening all had disappeared, with exception of one of the old pollen-masses of which a small part as yet peeped out.

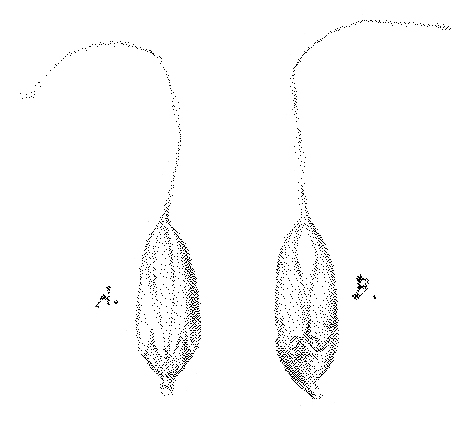

I enclose some seeds of our two species of Gesneria; they are, as you see, very small and may probably be blown at a great distance by the wind. Now there is in the seed-capsules a very fine contrivance preventing the seeds from falling to the ground without the action of the wind.18 The two valves remain united at the tip, and the pod only opens by two longitudinal slits, on its upper and under surfaces.

The slit on the under side (A) is shut by two rows of hairs inserted on the margins of the valves. So you may conserve the open pods for a long time without a single grain falling out, whereas by blowing you will drive them out in a moment. In some other cases, in which hairs on the valves, or hair-like processes on the orifice of the capsule are combined with exceedingly small seeds (as in a great number of Orchids, in most Hepaticae, in the peristome of mosses) their use seems to be different from what it is in Gesneria.19

I am to start to morrow for a botanical excursion on the continent, where I intent to spend a couple of weeks and whence I hope I shall not return without some interesting news.

With every good wish and profound respect believe me, dear Sir, very sincerely yours | Fritz Müller.

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Collected papers: The collected papers of Charles Darwin. Edited by Paul H. Barrett. 2 vols. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. 1977.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Cross and self fertilisation: The effects of cross and self fertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1876.

Crüger, Hermann. 1864. A few notes on the fecundation of orchids and their morphology. [Read 3 March 1864.] Journal of the Linnean Society (Botany) 8 (1865): 127–35.

‘Fertilization of orchids’: Notes on the fertilization of orchids. By Charles Darwin. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 4th ser. 4 (1869): 141–59. [Collected papers 2: 138–56.]

Higgins, Wesley E. 1997. A reconsideration of the genus Prosthechea (Orchidaceae). Phytologia 82: 370–83.

Orchids 2d ed.: The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects. By Charles Darwin. 2d edition, revised. London: John Murray. 1877.

Orchids: On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1862.

Origin 5th ed.: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 5th edition, with additions and corrections. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1869.

‘Three sexual forms of Catasetum tridentatum’: On the three remarkable sexual forms of Catasetum tridentatum, an orchid in the possession of the Linnean Society. By Charles Darwin. [Read 3 April 1862.] Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society (Botany) 6 (1862): 151–7. [Collected papers 2: 63–70.]

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

Summary

Describes his experiments in fertilising Oncidium flexuosum and comparison with Notylia.

Has been examining Catasetum.

Encloses seeds of two species of Gesneria and describes hairs in the seed capsule. Hairs in other plants seem to have a different function.

Starting tomorrow for a botanical excursion on the Continent.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-5344A

- From

- Johann Friedrich Theodor (Fritz) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Desterro, Brazil

- Source of text

- Möller ed. 1915–21, 2: 104–9; DAR 157a: 104

- Physical description

- ALS 1p inc, encl

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 5344A,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-5344A.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 15